Dinosaurs sit at the crossroads between reptiles and birds, leading scientists to debate whether they were warm- or cold-blooded. A new study may have found the answer for different groups of dinosaurs, by analyzing metabolic markers from their breath in their bones.

For more than a century after their discovery, dinosaurs were categorized as slow, lumbering creatures and due to their comparison to reptiles, were assumed to be cold-blooded. But the idea of warm-blooded dinosaurs began to gain ground in the 1960s, with groundbreaking studies into the anatomy of giant sauropods and the discovery of Deinonychus, the agile predator that served as the inspiration for Jurassic Park’s Velociraptors.

In the new study, scientists developed a new method for studying the metabolic rates of animals, including extinct ones, based on clues left in their bones from how much oxygen they breathed.

An animals’ metabolism basically boils down to how effectively it converts oxygen into energy. Warm-blooded or endothermic animals have high metabolic rates, requiring them to breathe in larger amounts of oxygen and eat more food to keep their body temperature up. Cold-blooded or ectothermic creatures, on the other hand, have a lower metabolic rate, so they breathe and eat less but instead rely on heat from their environment to keep warm.

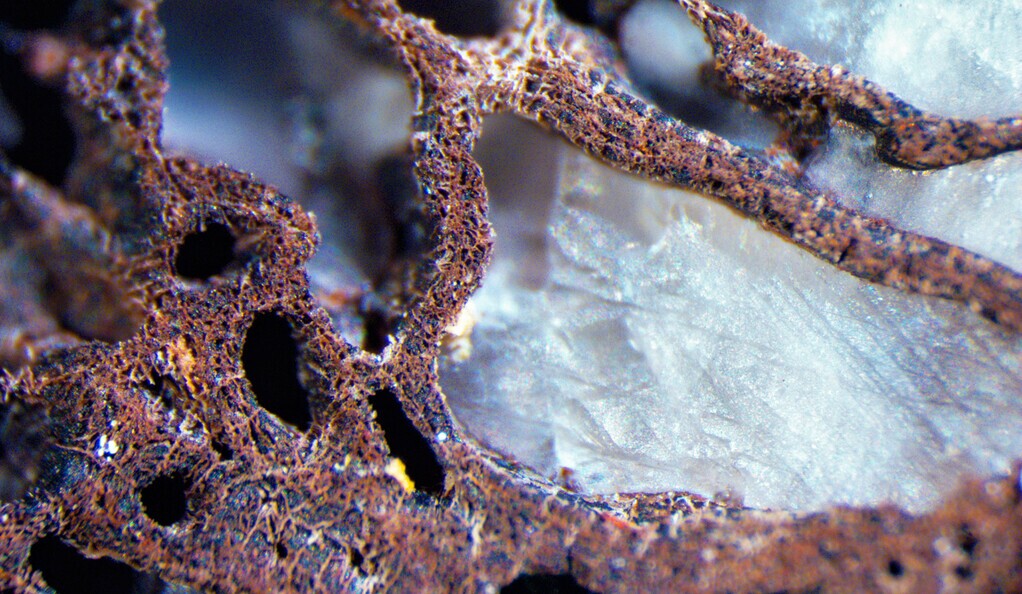

When animals breathe, it triggers a cascade of biological reactions that leaves molecular waste products in its bones. The amount of this waste scales directly with the amount of oxygen breathed, effectively keeping a record of whether the animal was warm- or cold-blooded. And importantly, these markers survive the fossilization process.

J. Wiemann

So for the new study, the scientists used techniques called Raman and FTIR spectroscopy to examine these molecular markers in the femurs of 55 groups of animals. That included extinct animals like dinosaurs, flying pterosaurs and marine plesiosaurs, as well as modern birds, mammals and reptiles. Since the metabolism of the living groups are well known, the team could compare the molecular profiles of their bones to those of the extinct animals, and infer what their metabolic rates might have been.

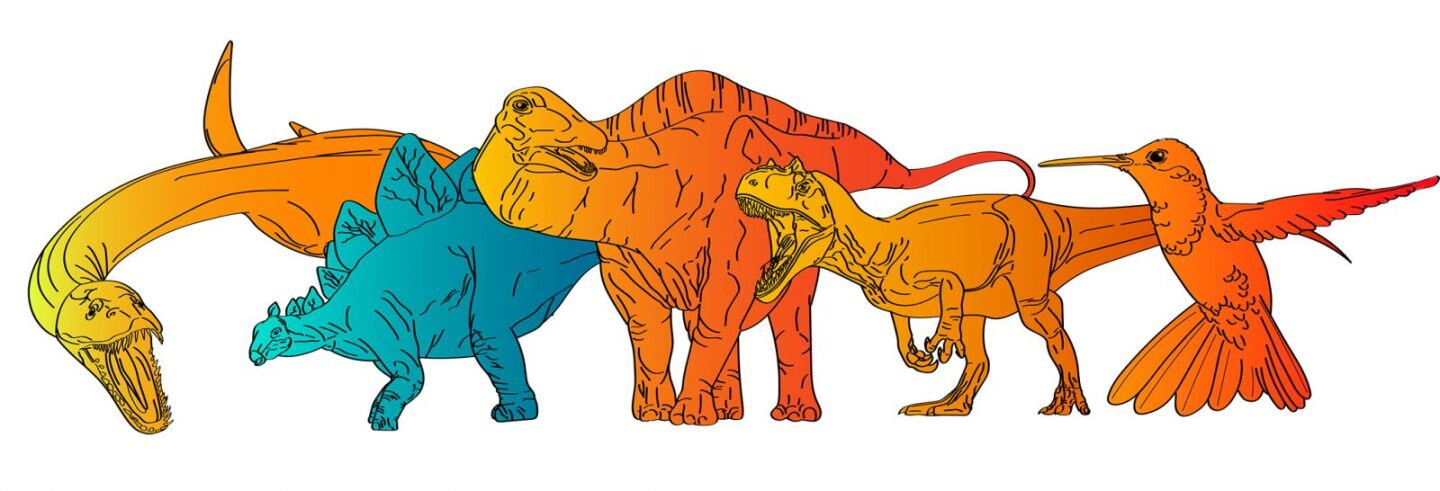

And the results were fascinating. Most species were found to be warm-blooded, including the pterosaurs, plesiosaurs, sauropods (long-necked dinosaurs like Brachiosaurus) and theropods (predatory dinosaurs like T-rex). Some of them even showed metabolisms higher than mammals, and closer to birds. Others, like Stegosaurus and Triceratops, seemed to have lower metabolic rates on par with modern cold-blooded reptiles, which could provide insight into their lifestyles.

J. Wiemann

“Dinosaurs with lower metabolic rates would have been, to some extent, dependent on external temperatures,” said Jasmina Wiemann, lead author of the study. “Lizards and turtles sit in the Sun and bask, and we may have to consider similar ‘behavioral’ thermoregulation in ornithischians with exceptionally low metabolic rates. Cold-blooded dinosaurs also might have had to migrate to warmer climates during the cold season, and climate may have been a selective factor for where some of these dinosaurs could live.”

The warmer-blooded animals, however, would have led more active lives bolstered by larger and more frequent feeding. Giant sauropods, for example, may have been more or less constantly chowing down on leaves.

The research provides intriguing new insights into the physiology and even behavior of dinosaurs and other extinct species, and provides scientists with a new tool for studying them.

The research was published in the journal Nature.

Sources: Field Museum, Yale University

Source of Article