The liver performs many vital functions in the body, so its cells are quick to regenerate. Now, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh have discovered just how persistent those cells can be. In tests in pigs with severe liver damage, functional new backup livers were found to grow in the animals’ lymph nodes.

Hepatocytes are the main functional cells in the liver, performing the various functions of the organ such as filtering blood from the digestive tract and producing bile. While these cells are normally experts at replenishing themselves, that gets a bit tricky during the end stages of liver disease, when scar tissue chokes them out.

“The liver is in a frenzy to regenerate,” says Eric Lagasse, senior author of the study. “The hepatocytes try to repair their native liver, but they can’t and they die.”

But in previous work, Lagasse discovered a remarkable survival strategy. In tests in mice with malfunctioning livers, the team injected healthy hepatocytes into the lymph nodes. Strangely enough, the cells thrived and actually formed a kind of backup liver that carried out many of the main organ’s functions.

“It’s all about location, location, location,” says Lagasse. “If hepatocytes get in the right spot and there is a need for liver functions, they will form an ectopic liver in the lymph node.”

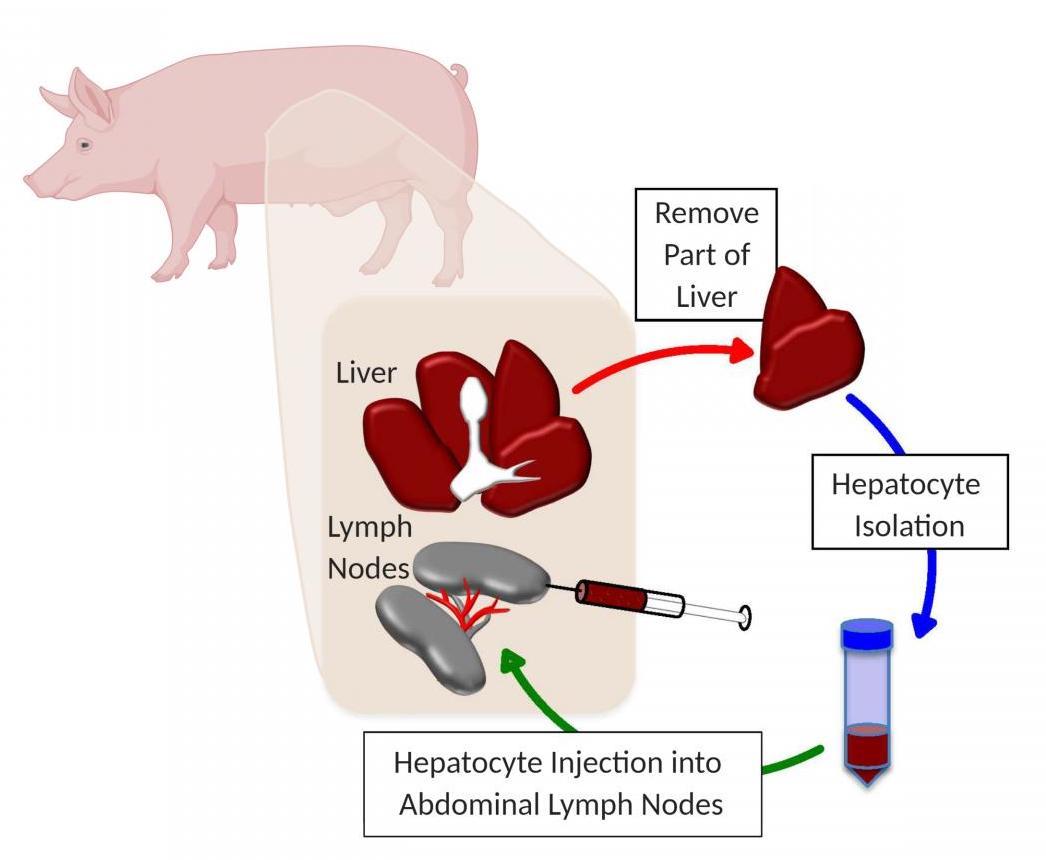

The researchers wanted to investigate whether this same process would occur in larger animals too, so for the new study they adapted the experiment for pigs. The team recreated liver disease in the animals by diverting blood away from the organ. They then extracted hepatocytes from a healthy sample of liver tissue, and injected them into the pigs’ lymph nodes.

UPMC

Sure enough, liver function was partially recovered in all six pigs. When the team examined the lymph nodes, they found that hepatocytes had settled in well, and had actually also grown bile ducts and vasculature. These auxiliary livers were also found to grow bigger in pigs with more severe tissue damage.

The team says that this result suggests that the new tissue growth isn’t out of control, in the way cancer is. Instead, it appears that the body is trying to get back to the optimum amount of liver cells it needs.

Whether or not this phenomenon works in humans will be explored next, the team says. If so, one day injecting hepatocytes into lymph nodes could be a useful treatment for patients with liver failure or advanced disease, to help buy time for a whole organ transplant.

The research was published in the journal Liver Transplantation.

Source: University of Pittsburgh Medical Center via Eurekalert

Source of Article