While most people attempting to lose weight will know that there is an optimal “zone’’ based on the heart rate achieved during different activities, at which fat metabolizes most efficiently. However, it’s generally a one-size-fits-all approach based on age. Scientists out of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai argue that while this method narrows down the parameters of the fat-burning zone, there’s still a lot of individual variation that could in fact mean some people are on either side of their heart-rate window.

“People with a goal of weight or fat loss may be interested in exercising at the intensity which allows for the maximal rate of fat burning,” said lead author Hannah Kittrell, a researcher at Icahn Mount Sinai. “Most commercial exercise machines offer a ‘fat-burning zone’ option, depending upon age, sex, and heart rate. However, the typically recommended fat-burning zone has not been validated, thus individuals may be exercising at intensities that are not aligned with their personalized weight loss goals.”

Those zones are often split into four or five overall stages, ranging from the first zone that is best for improving health or when a fitness program is being started. It features activities such as walking, swimming and easy cycling, with the aim to have your heart rate at 50-65% of its maximum. At the other end of the spectrum is the anaerobic zone, which includes high intensity exercise such as fast-paced running and cycling. Your heart rate in this zone should be 80%-100% of its maximum.

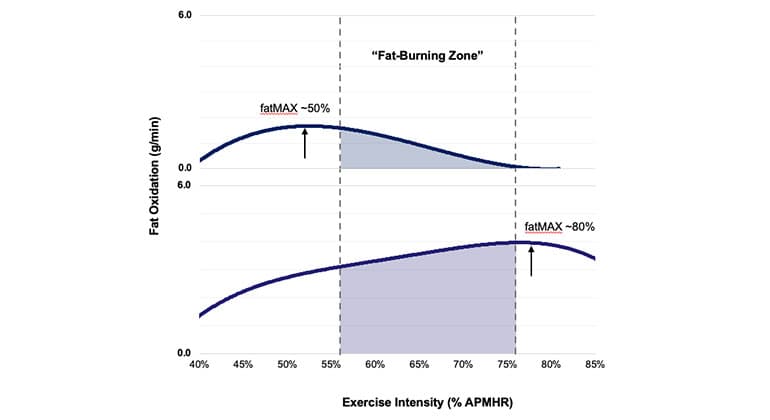

Between these two, however, there’s an optimal fat-burning zone, which is usually 55-75% of your maximum heart rate. At this stage, your body is burning up to 85% of the calories from fat stores. Once you exceed this zone, your body needs fuel faster – fat takes some time to burn and use as energy – so you’ll instead be burning carbohydrates. While this is still certainly not a bad thing for fitness, cardiovascular health and lowering the risk of many diseases, it’s not the most efficient if you’re trying to shift pounds compared to exercising at lower intensities.

In this study, scientists found that the usual way for determining your target heart rate for entering the fat-burning zone – by subtracting your age from 220 to determine your maximum heart rate and then working out 55-75% of that – could be more of a ballpark estimate than previously thought.

Using a FatMax scale, which measures the efficient fat-burning zone, a clinical exercise test on 26 individuals revealed that heart rates varied widely from the predicted rate based around the traditional formula, with a mean difference of 23 beats per minute.

Hannah Kittrell, Mount Sinai Physiolab and AIMS Lab at Icahn Mount Sinai

As such, people may not be getting the best out of their workouts and, the researchers add, believe an individual assessment as part of a whole exercise plan would be far more beneficial to see results.

The researchers now hope to apply these findings to a study that will assess how this personalized approach impacts weight loss and other metabolic health markers, like risks of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

“We hope that this work will inspire more individuals and trainers to utilize clinical exercise testing to prescribe personalized exercise routines tailored to fat loss,” says senior author Girish Nadkarni. “It also emphasizes the role that data-driven approaches can have toward precision exercise.”

The research was published in the journal Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Disease.

Source: Icahn School of Medicine

Source of Article