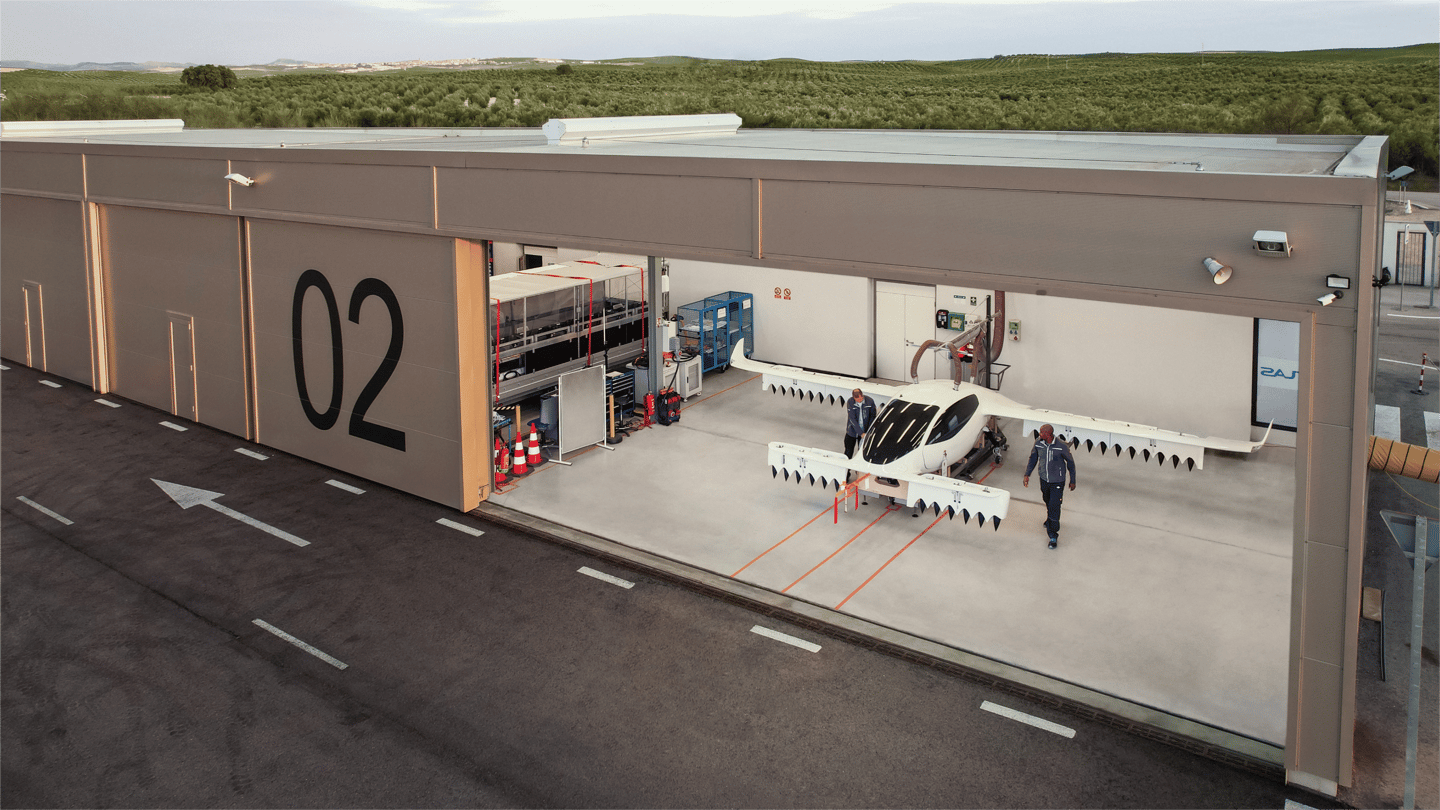

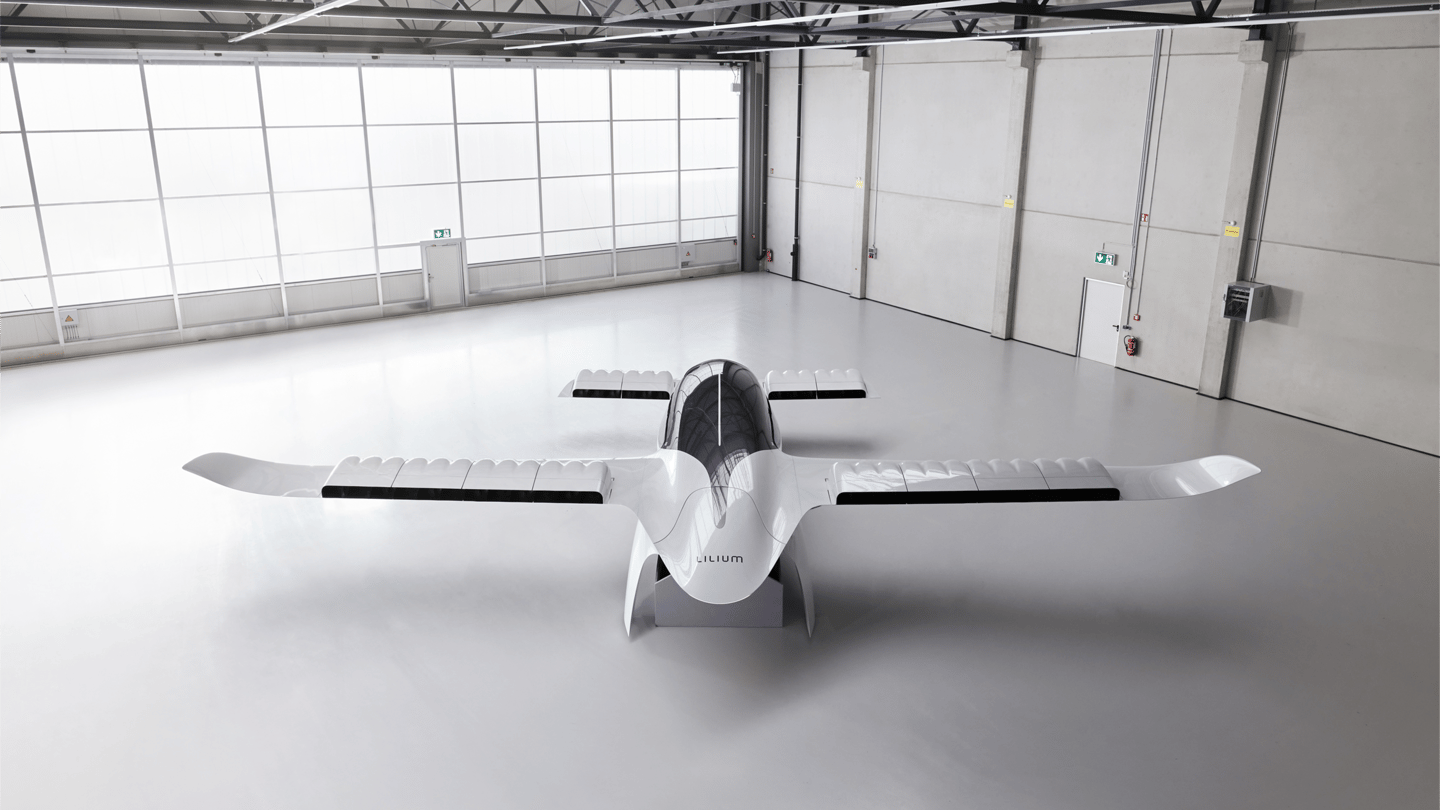

Earlier this year, on a trip to Europe, I dropped German eVTOL company Lilium a line, asking if I could drop in for a visit, and the team went out of their way to roll out the red carpet for me, arranging not only a sit-down with with co-founder Daniel Wiegand, but also a tour of the company’s gleaming white soon-to-be manufacturing facilities with CTO Alastair McIntosh, a chance to see the stunning full-size Lilium Jet demonstrator in person with Head of Industrial Readiness Julie Spanswick, a look through the ground-based component testing center with Senior Engineer Lukas Wollenberg, and a visit to the company’s design studio with Head of Product Design Thomas Vanciek.

But an absolute highlight was dropping into the simulator lab to chat with Senior Simulator Engineer Andreas Freiherr von Lepel, who threw me into a motion rig with a VR headset on, and gave me my first chance to fly the thing and experience its next-gen control scheme for myself.

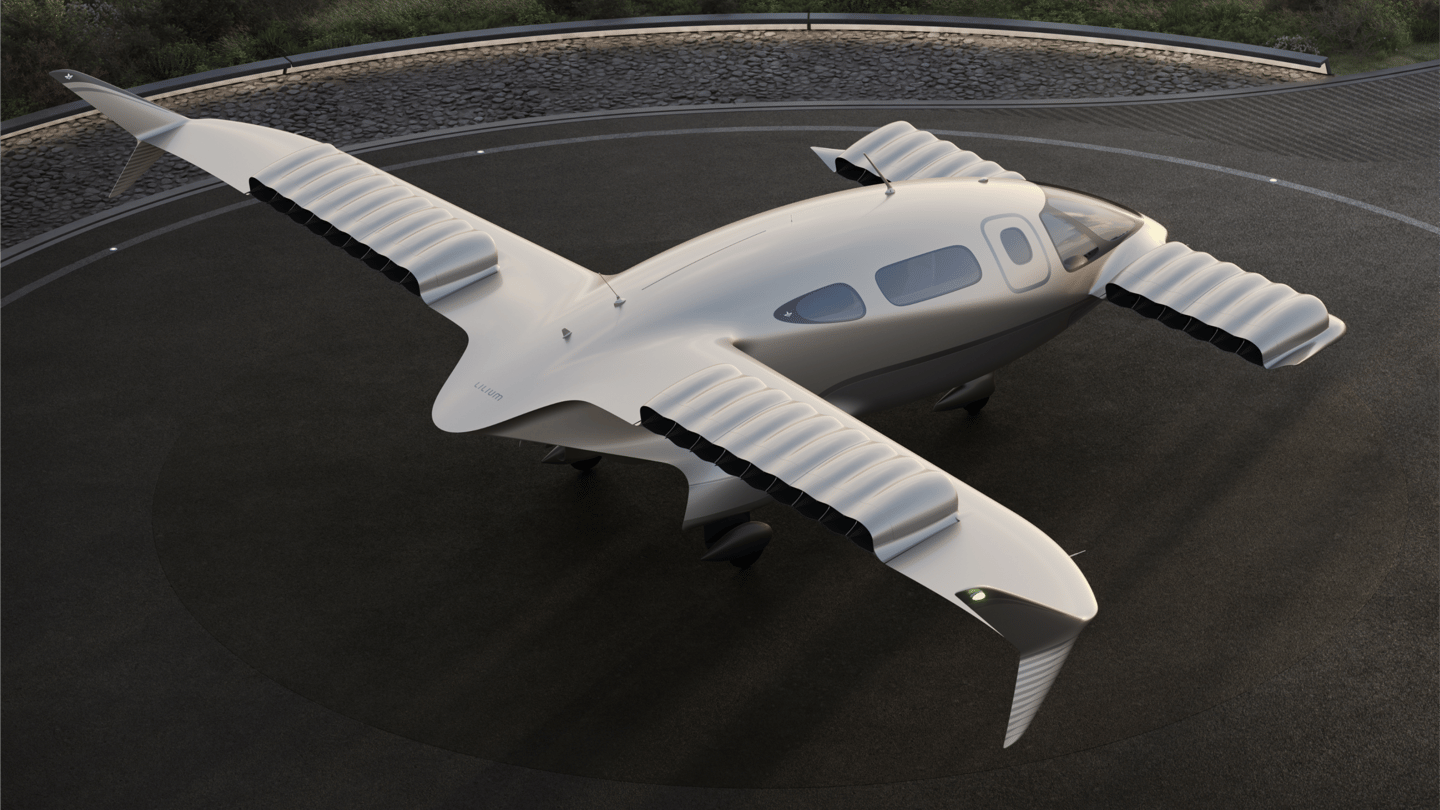

Why is this a big deal? Well, eVTOLs are in many ways a completely new type of passenger aircraft. Like the multicopter drones that inspired them, eVTOLs can take off and land vertically, with full control over yaw, pitch and roll movements during a hover. But many can also transition into fully wing-supported forward flight like an airplane – in Lilium’s case, by tilting its banks of electric propulsion jets between vertical and horizontal orientations during flight.

Lilium

There’s no way a pilot could control the motor speed and tilt of each of these little fan banks manually, so it’s all done through an intelligent fly-by-wire flight control system that monitors the aircraft’s dynamic position through all sorts of sensors, makes continuous adjustments on the fly to compensate for wind gusts and weight shifts in the cabin, and interprets a pilot’s control inputs on top of all this to make final decisions on what the fans and tilting banks will do.

So what you should have at the end of all this is an aircraft that just about anyone could fly – much like a toy drone that’s capable of carrying seven people at a time. It needs to run a control scheme that gives the pilot full control over fine hover maneuvers in VTOL mode, as well as the ability to soar, bank and glide like an airplane, and it needs to seamlessly manage the transitions between these flight modes, in a way that’s completely intuitive and easy to learn.

Lilium

That’s no simple task, so I’ve been fascinated to find out exactly what flying one will be like once they begin hitting the skies in bulk.

I wasn’t able to take photos of the simulator, but if you’ve seen the mid-size, multi-axis motion rigs people are using for driving games and flight simulators, that’s roughly what we’re talking about. Without a screen to look at, the VR headset allows me to look around a virtual cabin, matched component-for-component against what’s being built for the company’s Phoenix prototype. It also lets me look out the windows at a simulation of Manhattan from a dock-side vertiport pad, and also to look out at the ground through glass lower panels around my feet and legs.

Lilium Jet | Cabin Design Series | Hear from Andrew

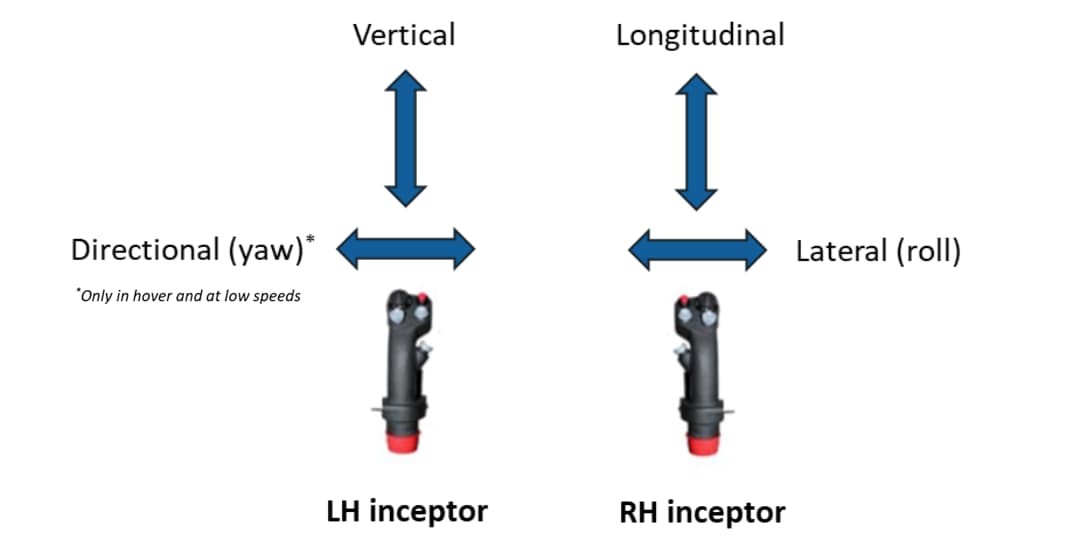

Lilium’s control scheme is pretty simple: a pair of joysticks, which it calls inceptors. “The controls are a little like a mix between a helicopter and a fixed-wing,” von Lepel tells me as I get settled into the cockpit. “The right inceptor controls your horizontal movement, a bit like the cyclic stick in a helicopter. Moving the left inceptor forward and back controls your vertical movement, so it’s something like the collective lever in a helicopter. But there are no foot pedals, so while you’re hovering, you can also control yaw and turn the aircraft around by moving the left inceptor to the left and right.”

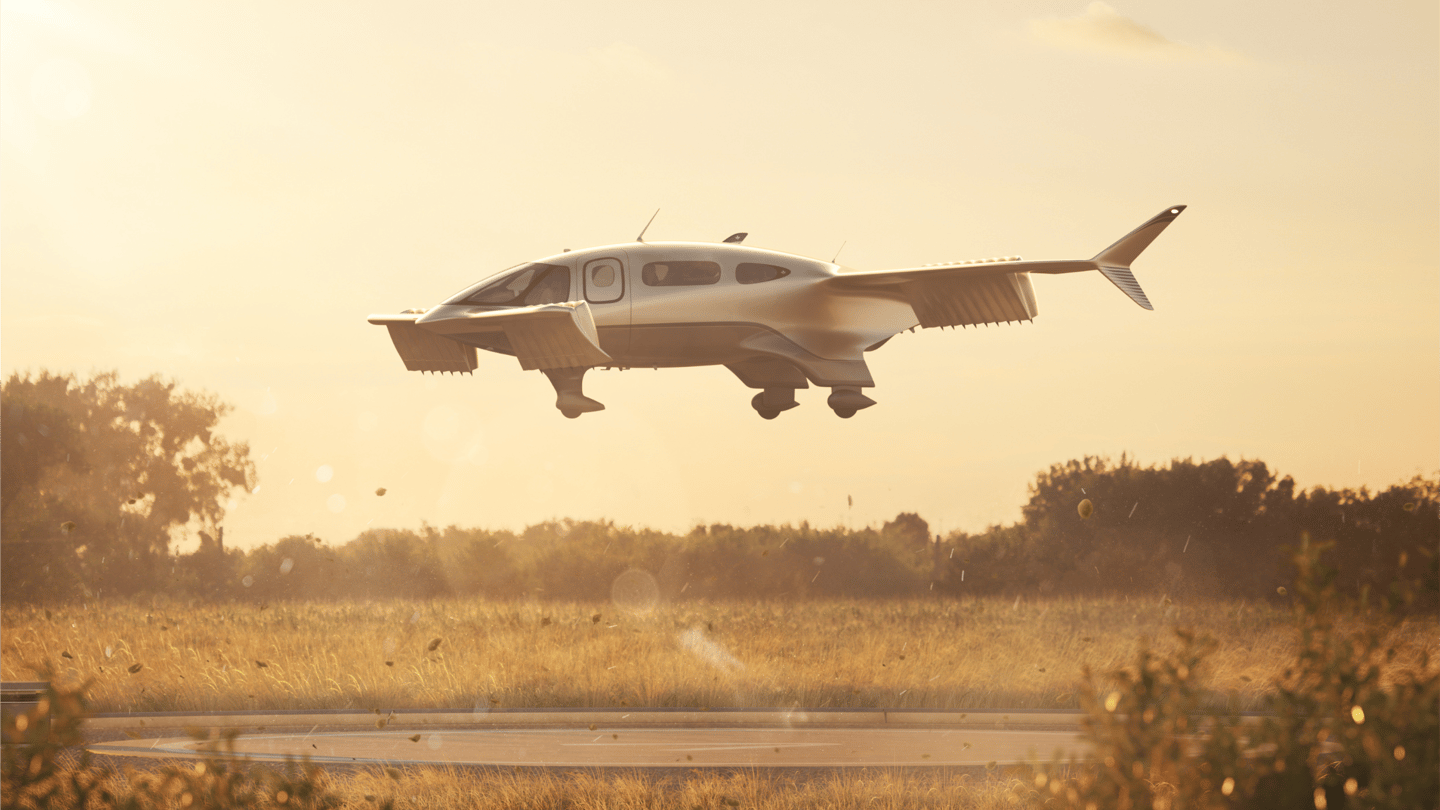

That’s enough to get me going, and von Lepel tells me to pull back on the left stick and get the Lilium jet off the ground. I do. More than 30 little jets on the aircraft’s four wings spin up quickly around me with a noisy electric whine, and the aircraft smoothly lifts off to a low hover.

Messing around here with the right stick, it becomes pretty clear that pilots will need to be careful with sideways movements, since the roll motion when this big drone tilts left or right can be pretty unsettling on the stomach if you’re at all ham-fisted on the joystick. And it does feel easy to push that stick too far, too fast. “That’s a compromise,” says von Lepel. “Fixed-wing pilots have much more resistance on the sticks, and helicopter pilots much less. So our settings are a compromise between the two.”

Lilium

It’s impressively agile, though. “I measured last week,” says von Lepel as I look out the window at the right canard, watching the propulsion bank tilt back and forth over the Hudson river as I maneuver around. “It’s 123 milliseconds from a pilot input to the output of the aircraft. Because of our very small fan discs, we have a very high disc load. That’s a disadvantage in hovering, because they use more energy. But one advantage is that they spin up really fast, so it’s very responsive.”

At any time, if you get yourself into trouble, you can always just let go of the sticks. At slow speeds or in a hover, the flight controller will simply stabilize the aircraft and hold position and altitude if you take your hands off. That’s reassuring, but trusting the thing enough to take my hands off the controls while I’m floating 40 feet (12 m) up in the air feels like quite an act of faith, even in the simulator. I remind myself that the controls are a digital illusion, just like the altitude, and the computer’s the one flying this thing anyway.

“OK, so right stick forward,” von Lepel tells me, “and go for like 60 or 70 knots (80 mph/130 km/h).” Righto. If sideways movement is a little lurchy, forward acceleration is completely smooth. Where most drone-style airframes need to pitch forward to move forward, the Lilium jet stays perfectly level and lets the propulsion jets tilt forward as I gather speed. The transition out of hover mode happens somewhere around 30 knots (35 mph/56 km/h), but as I’m being gentle on the right stick, it happens so smoothly that I’m in full forward cruise flight before I realize anything’s changed.

Lilium

But it has. In cruise flight, the Lilium Jet behaves more or less like a regular ol’ airplane. Well, at least, the airframe does; as far as the pilot’s concerned, it’s still totally digital and fly-by-wire, and the controls bear little relation to what you get in a fixed-wing.

Pushing the right stick forward remains a signal to accelerate, pulling it back slows you back down, and leaving it in a neutral position will simply maintain your current airspeed. Moving the right stick to the sides still results in a roll movement, but now that you’re supported by the wings, it’s a much more natural and comfortable feeling as the plane banks into turns.

But it’s a managed bank with a maximum angle in place; there are no barrel rolls here. If you let the stick spring back to neutral, the jet will smoothly right itself. And Lilium has designed it such that as you bank, the distributed propulsion system puts a little extra mustard on the outside wing’s props, to swing the nose of the plane into the turn a little quicker without the need for a rudder.

Lilium

In cruise flight, the Jet stops responding to yaw commands, but otherwise the left stick maintains the same overall function: pull it back to gain altitude, push it forward to bring the aircraft downward. Mind you, this feels completely different in practice; pulling back on the left stick makes the plane pitch backward as it rises, and pushing forward sends the nose down, both to a managed maximum angle.

This is the control that confuses my brain the most; I’m expecting the right stick to handle pitch and roll, with the left becoming more like a throttle. But it doesn’t take long to get the hang of things, and before long I’m merrily banking between skyscrapers and making a menace of myself.

That’s not how these will be flown in practice, of course, so von Lepel tells me to head out over the water for a sight-seeing hairpin around Lady Liberty out in the river. And once your heading, airspeed and altitude are set, there’s really nothing to do but let go of the sticks and enjoy the view; the Jet flies itself in a straight and level line.

Lilium

We approach the Statue of Liberty at the Jet’s managed top speed of 136 knots (157 mph/250 km/h), then I pull the right stick back to slow down. What the hell, I pull it fully backward, and the electric jets scream as the aircraft pulls up, making a fairly rough transition into a pitched-up hover mode, slowing all the way to a surreal, stationary hover with a great view up the Statue’s nose. “Totally stable,” says von Lepel. “Even with a crosswind from the side, you’d stay right here on the spot.”

Pushing the stick forward again, the Jet quickly gathers speed, and I bank it back around at about 50 knots (58 mph/93 km/h) to head back for the city towers. Von Lepel tells me to head for the One World Trade Center, and land on top.

Approaching from above, I reduce speed as I drop down toward the pad. eVTOL pilots will be well aware of how much battery these birds burn in a hover, so the art will be in staying on the wing as long as possible, and keeping the VTOL phase of flight as short as possible. Looking down at the helipad on top of the building, it’s a piece of cake putting the Jet down right in the big yellow circle, no harder than landing a drone. It touches down with a minimum of fuss.

Lilium

“Well done,” says von Lepel, “Your approach was just like we would do it. We don’t want to waste too much time hovering around. So we glide in slowly like a fixed-wing, and come down sort of diagonally rather than vertically. You see the H on the helipad and come down, and you’re only thrust-supported for maybe 20 seconds. So that’s 15 minutes from takeoff, and you’ve flown around, had a meeting with the Statue of Liberty, flown between high-rise buildings in New York City and landed safely on top of a skyscraper. What more could you want?”

It’s possible to fly the Lilium Jet in a way that’s quite rough and uncomfortable in the cabin. It would definitely be possible for Lilium to engineer these situations right out of the flight controller and make everything super smooth, but at the moment the company doesn’t plan to; pilots, says von Lepel, universally tend to opt for more control authority where it’s available. They’d prefer to learn to fly these things smoothly, but retain the ability to roll hard sideways in a hover or pull up to a gut-wrenching stop if they need to; in an emergency, safety and control trumps comfort, and it’s hard to disagree with that.

The control scheme is still under development, but from my brief experience at the sticks, it’s clearly an order of magnitude easier to fly this eVTOL than to pilot a fixed-wing, or wrangle the four-limbed control system of a standard helicopter. You can fly it perfectly safely, if not particularly smoothly, with zero experience and just a quick chat to guide you.

Lilium

Training eVTOL pilots will still take time; there’s a lot more to learn than just how to fly the aircraft. But the flying part might be easier than anything else in the sky, which is handy, since eVTOLs are expected to propagate in large numbers over the coming decades.

Eventually (or indeed, initially – at least, in China) there’ll be no need for these things to carry the weight and expense of human pilots. Truth be told, autonomous flight control coupled with remote control backup pilots is probably already well enough advanced to take over. But European and American air authorities are moving slowly and steadily on this new generation of aircraft, and it could be a decade before they start allowing autonomous eVTOLs to start taking passengers.

So if the eVTOL segment takes off like it’s projected to, then within a few years there’ll be a fair few eVTOL pilot jobs going around for aircraft like the Lilium Jet, the Joby S4, the Archer Midnight and a host of other contenders. It certainly doesn’t look like the kind of gig you’d take for long-term job security; the robots will take it sooner rather than later. But these aircraft should be pretty easy and pleasant to fly, and you’ll certainly have the king of all views from the office.

Check out Lilium’s sub-scale test aircraft achieving its 250-km/h (155-mph) top speed in the video below.

Faster than the Harris Hawk | Lilium

Huge thanks to Andreas, Meredith, Christine, Daniel and the Lilium team for putting this visit together for me and making the simulator available.

Source: Lilium

Source of Article