Scientists have been able to track the entire life of a mammoth that lived more than 17,000 years ago, right down to the week. By studying the isotopes in different parts of its tusk, the team figured out where in Alaska it likely was at any given point of its 28-year life.

During the Pleistocene epoch, mammoths were spread wide across the world, ranging from northern Europe and Asia, through Russia and into North America. But how far would an individual mammoth have traveled during its lifetime? The new study, led by scientists at the University of Alaska, have now answered that question in surprising detail.

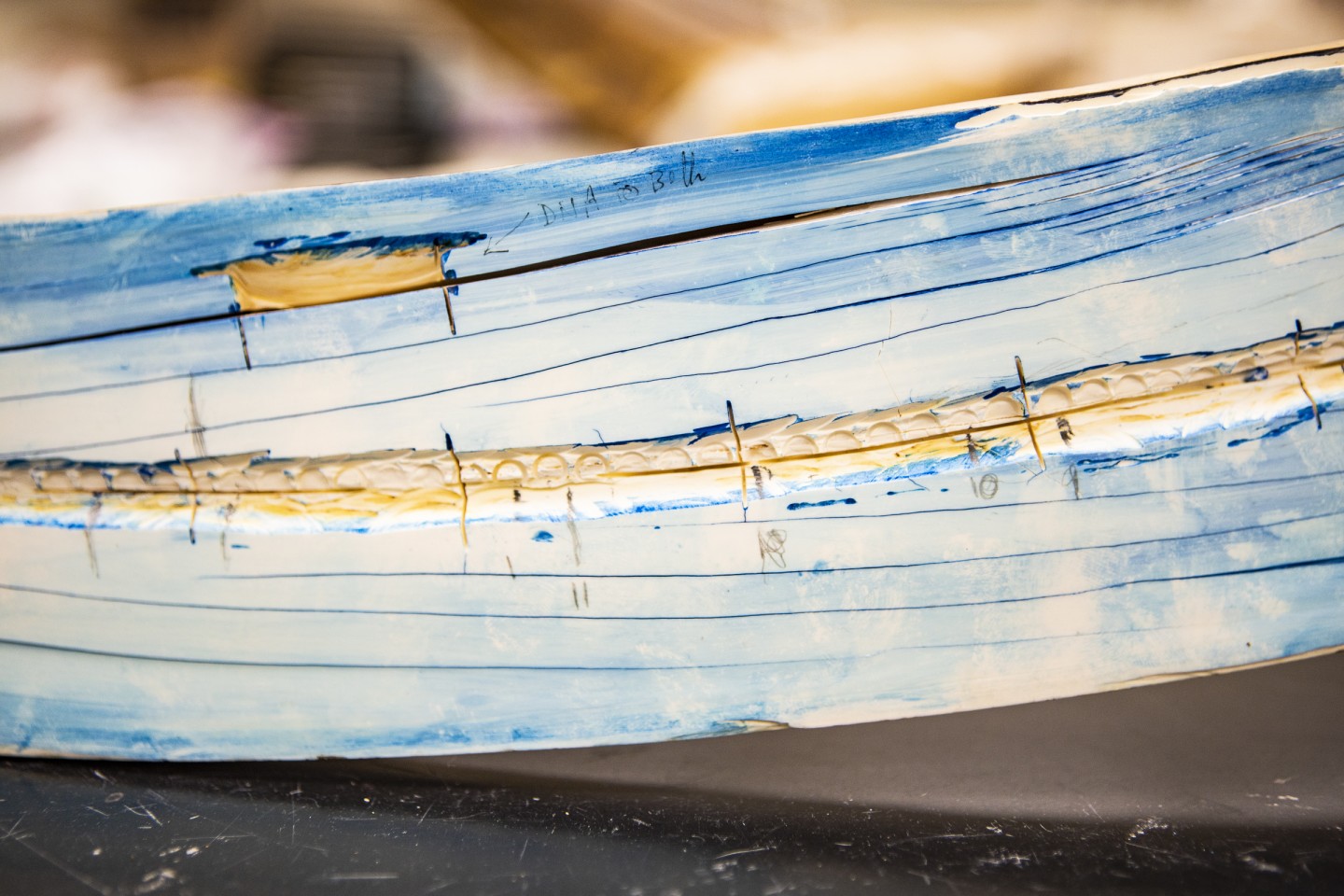

To do so, the researchers closely examined a 6-ft (1.8-m) long mammoth tusk dating back around 17,100 years. Mammoth tusks grow by adding layers of tissue almost daily, forming rings like a tree that can reveal detailed information. So the team split the tusk down the middle, then collected data from 400,000 different points along the length of it.

UAF/ JR Ancheta

The main thing the researchers analyzed were oxygen and strontium isotopes, which can act almost like an ancient GPS. Different regions have different isotopic signatures, which start in minerals deep underground and make their way to the surface, into plants and water, and then into animals that consume those plants and water.

Previous studies had produced an isotopic map of Alaska by analyzing isotopes in the teeth of hundreds of small rodents, which don’t travel far in their lifetimes and so represent a local area. The researchers can then compare isotopic signals from each section of the mammoth’s tusk to this map, to get an idea of where the mammoth most likely roamed throughout its life.

“From the moment they’re born until the day they die, they’ve got a diary and it’s written in their tusks,” says Pat Druckenmiller, an author of the study. “Mother Nature doesn’t usually offer up such convenient and lifelong records of an individual’s life.”

To piece together the mammoth’s life, they started at the end. That’s where we have the clearest picture of where it was, since its remains were found on Alaska’s North Slope. Working backwards, the scientists then looked at the isotopic signature of where the mammoth was about a week before death, then searched the map for the best match in a nearby region. A spatial model then worked backwards stepwise to determine the most likely routes the mammoth might have taken, accounting for distance and geographical barriers like cliffs. Genetic studies showing that the animal was a male, and lived to 28 years of age, also helped to add context to his life story.

UAF/ JR Ancheta

And from this sprang an intriguing tale. The mammoth seems to have spent his early years in the Yukon River basin and the interior of Alaska, trekking back and forth between several territories in a predictable pattern. The team says that this behavior seems to be migratory, like modern elephants, and suggests it was living as part of a herd.

“It’s not clear-cut if it was a seasonal migrator, but it covered some serious ground,” says Matthew Wooller, senior author of the study. “It visited many parts of Alaska at some point during its lifetime, which is pretty amazing when you think about how big that area is.”

But things changed drastically at about age 15. There’s a sudden shift in the isotope patterns that indicate it was traveling a bit more randomly, which may mean that it had come of age and left the herd – another similarity to modern elephants. This continued for about a decade.

In the last few years of its life, the mammoth spent almost all of its time in a smaller territory near the northern coast of Alaska. Sadly, the isotope patterns recorded at the base of the tusk – meaning the most recent – were higher in nitrogen, which is a sign of starvation in mammals. The team concludes that this was the most likely cause of death.

In addition to enabling an intriguing peek at the life of an ancient animal in such detail, the researchers say that some of the data could have applications for the future.

“The Arctic is seeing a lot of changes now, and we can use the past to see how the future may play out for species today and in the future,” says Wooller. “Trying to solve this detective story is an example of how our planet and ecosystems react in the face of environmental change.”

The research was published in the journal Science.

Source: University of Alaska Fairbanks via Nature

Source of Article