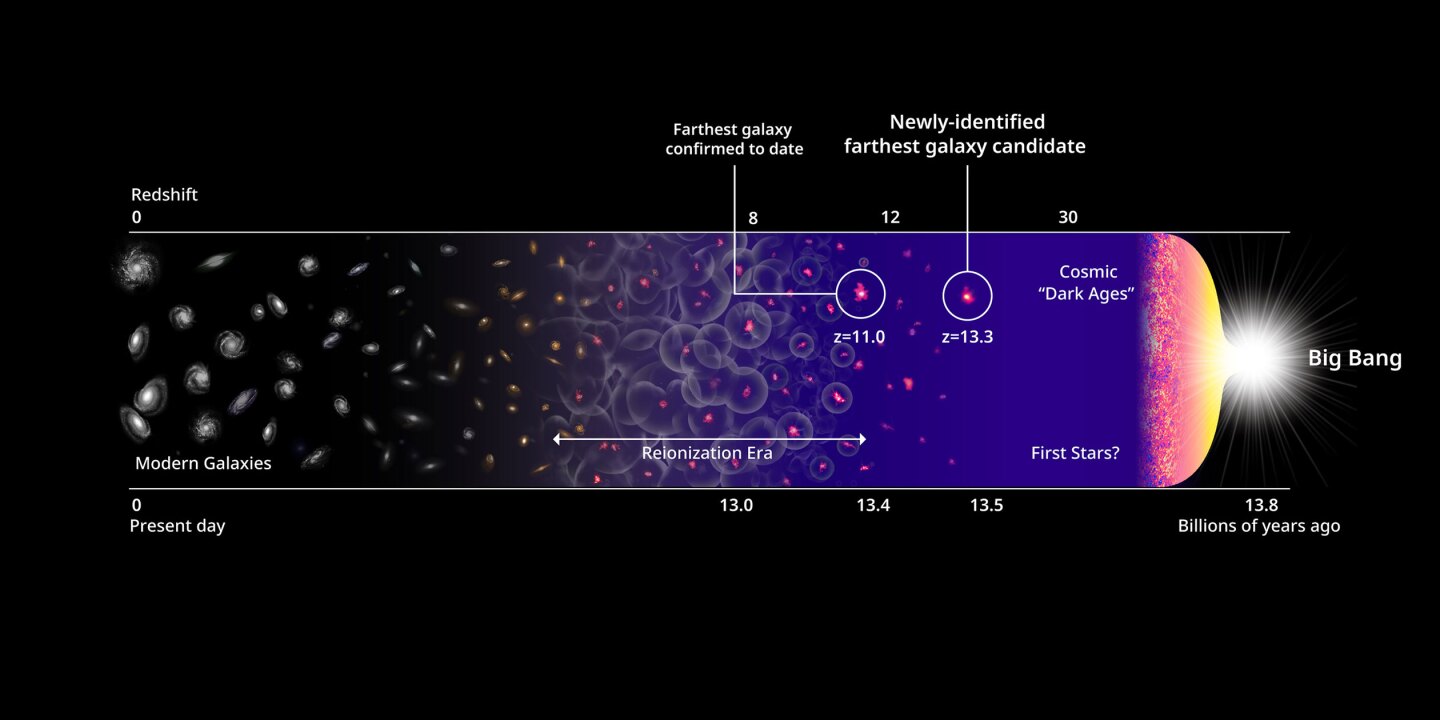

Astronomers have discovered the most distant object ever seen – a strange galaxy some 13.5 billion light-years away. Known as HD1, the galaxy may house a never-before-seen population of stars, or a supermassive black hole mysteriously ahead of its time.

HD1 and a slightly closer galaxy called HD2 were discovered using the Spitzer, Subaru, VISTA and UK Infrared telescopes, before the incredible distance was confirmed using ALMA. At 13.5 billion light-years away, HD1 is not just the most distant galaxy detected, but the most distant object of any kind ever seen. It pips the previous record holder, a galaxy called GN-z11, by more than 100 million light-years. Recently, astronomers discovered the most distant individual star ever found – Earendel, which lies 12.9 billion light-years away.

To look deep into space is to look back in time, and so that means we’re seeing HD1 as it was 13.5 billion years ago, which was just 300 million years after the Big Bang. As such, the galaxy could provide astronomers with a fascinating new glimpse into the early history of the universe – and it’s already revealing some strange insights.

Harikane et al., NASA, EST and P. Oesch/Yale

It turns out that HD1 is extremely bright in ultraviolet wavelengths, which would suggest that some very energetic processes are occurring in the galaxy. The astronomers have two leading hypotheses about what could be going on there.

The first is that HD1 is busily forming new stars. But to produce that much light, not only would the galaxy need to be birthing stars far more quickly than expected, but they would be of a hypothetical type known as Population III stars. If confirmed, this would be the first direct detection of these early stars.

“The very first population of stars that formed in the universe were more massive, more luminous and hotter than modern stars,” said Fabio Pacucci, lead author of the study. “If we assume the stars produced in HD1 are these first, or Population III, stars, then its properties could be explained more easily. In fact, Population III stars are capable of producing more UV light than normal stars, which could clarify the extreme ultraviolet luminosity of HD1.”

The second possibility is that a supermassive black hole with a mass about 100 million times that of the Sun, lurks at the heart of HD1, and the excess UV light is produced as it chows down on dust and gas. But that would make it the earliest known supermassive black hole by quite a margin, which would raise questions about how such a monster grew so big so quickly.

Whatever’s going on in HD1, the team plans to investigate using the recently launched James Webb Space Telescope. This infrared instrument is specifically designed to probe farther back in space and time than any telescope before it, and is perfectly suited to solving mysteries like this.

Two papers on the discovery have been accepted for publication, one in The Astrophysical Journal and another in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters.

Source: Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

Source of Article