A new study published in the The Journal of Psychopharmacology is reporting the results of a large clinical trial testing the short- and long-term safety of administering psilocybin in a group setting. Exploring the psychedelic therapy in groups of up to six people, the trial found no detrimental effects from simultaneous administration of the drug.

Group therapy is often a key component of many psychiatric treatments, so it certainly is no surprise that researchers are beginning to investigate the viability of incorporating psychedelic drugs into that particular therapeutic context. In the underground psychedelic community, group drug sessions have been common for decades, especially with ayahuasca, a traditional South American psychedelic brew that has become increasingly popular with Western tourists.

Back in the 1960s, before psychedelic research was shut down for decades, a number of studies looked at the effects of psilocybin and LSD when delivered in group settings. But since the dawn of the psychedelic renaissance in the 21st century almost all modern research has focused on individual psychedelic administration.

This new research, led by King’s College London and supported by Compass Pathways, is the first modern published study on simultaneous psilocybin administration in groups of up to six participants. The research is also the first randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial to explore the effects of group psilocybin dosing.

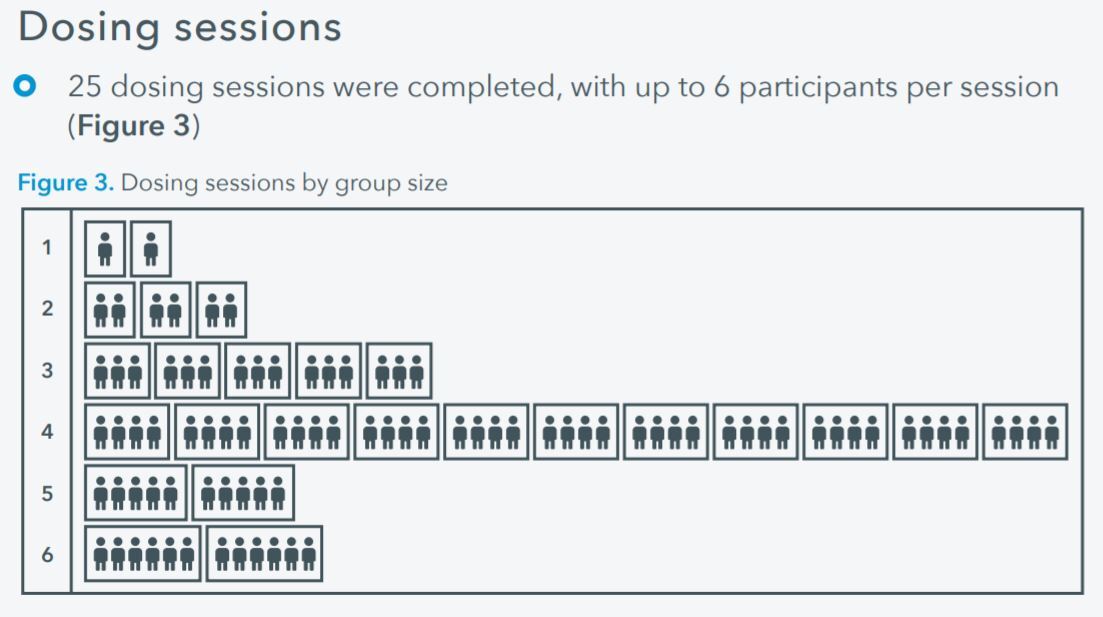

The main goal of this study was to assess the short- and long-term safety of administering psilocybin in different groupings of people simultaneously. The trial recruited 89 healthy subjects, with 60 receiving active psilocybin doses and 29 receiving a placebo. There were six different group permutations explored in the trial, including two sessions with six participants each.

COMPASS Pathways

Importantly, these sessions were not conducted in some kind of communal circle, but instead each participant was offered a relatively private space accompanied by their own therapist and with a lead therapist overseeing each session.

“The simultaneous dosing involved each participant having a private space, for example, a bed separated by curtains within the same room, so they could focus on their own experience with minimal distractions, especially as participants were encouraged to wear eyeshades, earplugs and/or earphones for the duration of the administration session,” the researchers explain in the study. “Participants communicated only with their therapists during the administration sessions.”

A number of cognitive and emotional tests were conducted over the 12-week follow-up after the psilocybin session. This allowed the researchers to conclude this mode of delivering psychedelic therapy sessions did not lead to any negative outcomes over the subsequent weeks.

“This rigorous study is an important first demonstration that the simultaneous administration of psilocybin can be explored further,” explains lead author on the new research, James Rucker. “If we think about how psilocybin therapy (if approved) may be delivered in the future, it’s important to demonstrate the feasibility and the safety of giving it to more than one person at the same time, so we can think about how we scale up the treatment.”

In 2019, when early data from this trial was announced, Compass Pathways’ Communications Officer Tracey Cheung told New Atlas via email that the motivation behind these group dosage experiments was primarily about exploring ways to streamline the treatment process. Scheduling more than one patient at a time could accelerate the pace of clinical trials, and Cheung also suggested this strategy may enhance patient access once the psychedelic treatment was approved and clinically deployed.

The new study reports no serious adverse effects were detected from the administration of psilocybin. However, it is important to note this trial was conducted in healthy young adults and not subjects with pre-existing psychiatric illness.

The study also reports no assessment was made regarding the efficacy of blinding. This issue, previously cited by some researchers as a major problem with modern psychedelic clinical studies, is briefly mentioned in the study as a potential reason why four subjects in the placebo group dropped out of the trial before it was complete.

Commenting on the new study psychedelic researcher Eduardo Schenberg, who did not work on this new trial, says he hopes this is the last trial of this kind to get away with not reporting on how many subjects guessed which group they were in. As discussed last year in a comprehensive research article by New Zealand researcher Suresh Muthukumaraswamy, the problem with blinding in placebo-controlled psychedelic research could be generating over-estimated results.

“I hope this will be the last ‘placebo-controlled’ psychedelic trial publication to be accepted without measuring and adequately reporting unblinding,” Schenberg tweets. “It’s time for expanded discussion about this approach, its epistemic assumptions and far reaching consequences.”

The new study was published in The Journal of Psychopharmacology.

Source: King’s College London

Source of Article