With Siberian heatwaves, rapidly declining ice and a warming trend that is three times the rate of the rest of the globe, the Arctic is feeling the brunt of climate change as much as any region on Earth. One glimmer of hope is what’s known as the “Last Ice Area,” a region where summer sea ice is expected to survive the longest and therefore act as a refuge for the wildlife that depends on it. But new research shows that even this bastion of hope is under threat.

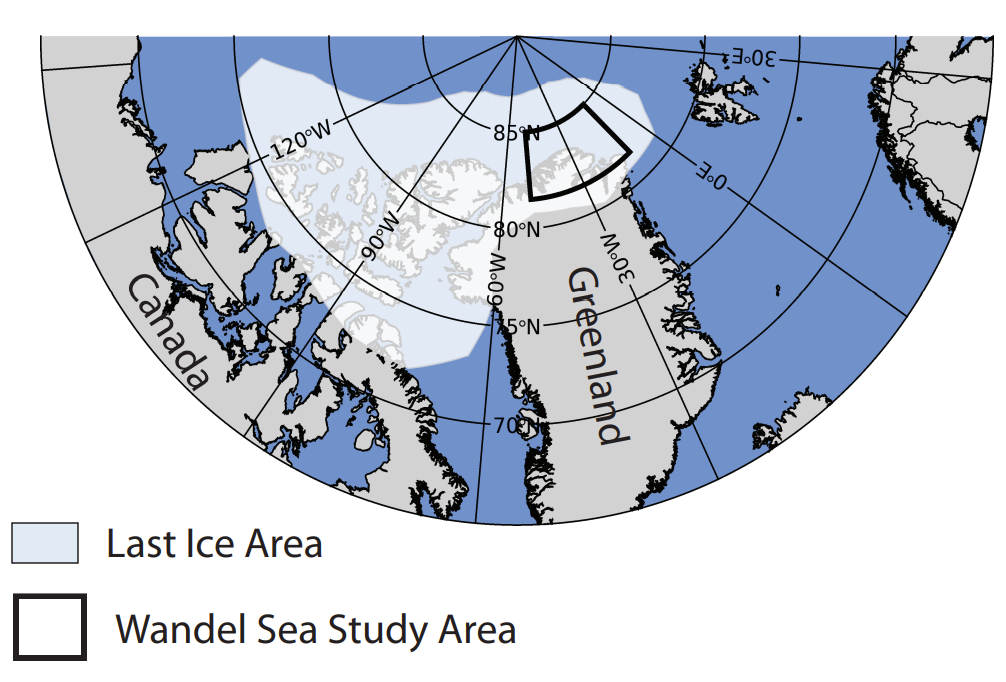

Record-breaking temperatures have coincided with record lows in Arctic sea ice coverage in recent years, with some scientists even warning that the rate of change taking place is so rapid and remarkable that the Arctic is entering an entirely new climate state. The Last Ice Area is a polar region to the north of Canada and Greenland that will be critically important in light of these trends, as the walruses, polar bears and seals that rely on sea ice for sustenance and shelter fight for survival.

“Sea ice circulates through the Arctic, it has a particular pattern, and it naturally ends up piling up against Greenland and the northern Canadian coast,” says lead author Axel Schweiger, a polar scientist at the University of Washington’s Applied Physics Laboratory. “In climate models, when you spin them forward over the coming century, that area has the tendency to have ice survive in the summer the longest.”

Schweiger et al./Communications Earth & Environment

Schweiger and his co-authors focused their attention on one patch of the Last Ice Area called the Wandel Sea, which has historically been blanketed year-round in thick, multiyear ice. As it has throughout the Arctic, the ice here has been thinning slowly. Satellite measurements taken in late local summer on August 14, 2020, however, have now revealed a record low of just 50 percent sea ice concentration.

This came as a surprise to the scientists, because the average ice thickness at the beginning of the summer was close to normal, and above average thickness was detected in the springtime.

As part of the study, the scientists drew on satellite data and sea ice models to tease out the reasons behind the record low. These models simulated the weather and conditions between June 1 and August 16, and found that unusual winds played a role by sweeping sea ice out of the area and contributed around 80 percent overall to the decline, while 20 percent of it was due to the multiyear ice thinning, which exposes more of the ocean to sunlight and causes the water to warm and melt surrounding ice floes.

Felix Linhardt/Kiel University

“During the winter and spring of 2020 you had patches of older, thicker ice that had drifted into there, but there was enough thinner, newer ice that melted to expose open ocean,” Schweiger says. “That began a cycle of absorbing heat energy to melt more ice, in spite of the fact that there was some thick ice. So in years where you replenish the ice cover in this region with older and thicker ice, that doesn’t seem to help as much as you might expect.”

While the findings don’t bode well for long-term health of this critical region of the Arctic, the scientists emphasize that the findings can’t be extrapolated to the entire area. There are many more questions still to answer, including how more open water in the Last Ice Area would affect the behavior of ice-dependent species. In any case, the revelation that the region is already being affected by global warming is certainly cause for concern.

“Current thinking is that this area may be the last refuge for ice-dependent species,” says lead author of the new author Axel Schweiger , “So if, as our study shows, it may be more vulnerable to climate change than people have been assuming, that’s important.”

The research was published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

Source: University of Washington

Source of Article