While all kinds of questions remain around how sperm travel and go about fertilizing eggs, they have generally been thought to propel themselves forward by moving their tails side-to-side like an eel. Scientists have tapped advanced 3D microscopy and high-speed cameras to paint a different picture of swimming sperm, one that upends this centuries-old perception and furthers our understanding of reproductive science.

The first detailed observations of sperm were recorded by Dutch scientist Antony van Leeuwenhoek more than 300 years ago. Using the early compound microscope he developed himself, the microbiologist used his instrument to observe what appeared to be a tail swishing back and forth to drive the sperm forward.

The new research carried out by fertility scientists at the University of Bristol and the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico suggests things aren’t exactly what they seem. The team used a mix of state-of-the-art 3D microscopy, mathematic modeling and high-speed cameras to reconstruct the movement of sperm tails in 3D, with some surprising results.

By using a microscopic-scale stage hooked up to a piezoelectric device to simulate the swimming environment, the team recorded the sperm in action at more than 55,000 frames per second using high speed cameras. According to the researchers, what they saw reveals that the common perception of sperm’s side-to-side propulsion method is an “optical illusion.”

polymaths-lab.com

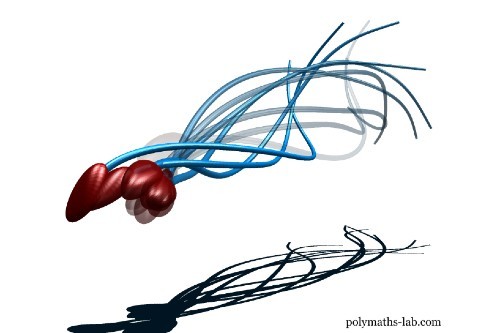

Instead, the team saw a wonky tail that actually only wiggles on one side. Left to its own devices, this asymmetrical tail movement would have the sperm simply swimming in circles. But the sperm instead accommodate for this through a rapid tumbling motion that distributes the energy on both sides and keeps them moving forward.

“Human sperm figured out if they roll as they swim, much like playful otters corkscrewing through water, their one-sided stoke would average itself out, and they would swim forwards,” says Dr Hermes Gadelha from the University of Bristol. “The sperms’ rapid and highly synchronized spinning causes an illusion when seen from above with 2D microscopes – the tail appears to have a side-to-side symmetric movement, ‘like eels in water.'”

The team believes the research can open up new pathways in the study of reproductive science. Much analysis of semen is carried out with 2D modeling, which means that it still presents as the centuries-old illusion of symmetry. This fresh 3D perspective of the intricate maneuvers taking place furthers our understanding of sperm biomechanics and, it’s hoped, will pave the way for further discoveries that illuminate the processes underpinning human reproduction.

“This discovery will revolutionize our understanding of sperm motility and its impact on natural fertilization,” says Dr Alberto Darszon from the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. “So little is known about the intricate environment inside the female reproductive tract and how sperm swimming impinge on fertilization. These new tools open our eyes to the amazing capabilities sperm have.”

The research was published in the journal Science Advances, while you video below offers an overview of the research.

Spinners, not swimmers: how sperm fooled scientists for 350 years

Source: University of Bristol

Source of Article