It’s assumed that as we get older our health will gradually deteriorate. Our bodies age, wrinkles form, metabolism slows, and our immune system weakens. But how much of what we consider to simply be natural aging is actually due to preventable environmental factors?

A striking new study led by researchers from Columbia University Irving Medical Center has found a strong link between exposure to air pollution and a weakening of the lungs’ ability to battle respiratory infections. The findings shed light on why older people are particularly vulnerable to respiratory diseases such as COVID-19 and influenza, and serve as a stark reminder of the importance of clean air.

The research began over a decade ago, as a study looking at immune cells in lymphoid tissue from deceased donors. Initial investigations turned up something unexpected: lung lymph node tissue from non-smokers looked very different to lymph nodes in other parts of the body.

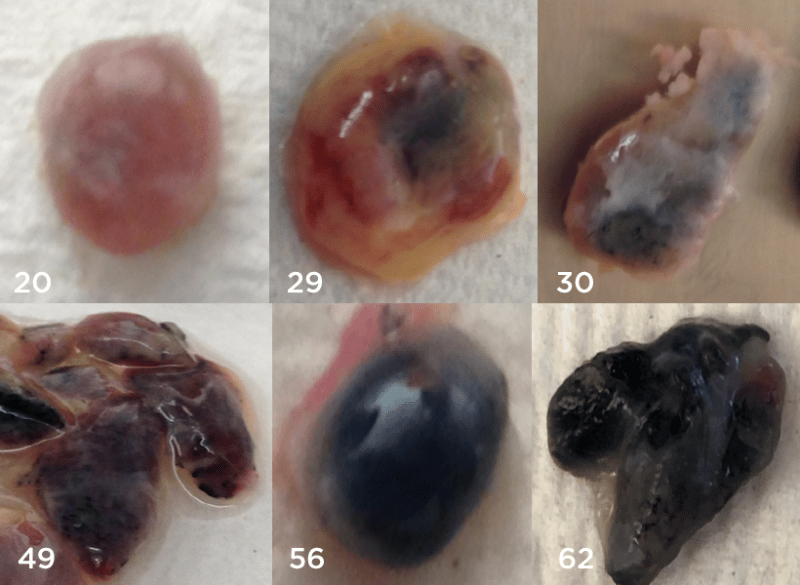

“When we looked at people’s lymph nodes, we were struck by how many of the nodes in the lung appeared black in color, while those in the GI tract and other areas of the body were the typical beige color,” explained Donna Farber, lead researcher on the project.

The researchers started to gather more lung lymph tissue from a variety of donors and quickly detected a pattern. The younger the lymph node, the lighter in color it was. And when the researchers took a closer look at the blackened lymph tissue they found it was packed with air pollution particles.

So this new study, published in Nature Medicine, set out to explore whether this chronic exposure to air pollution was slowly damaging lymph nodes over time, ultimately impairing a person’s immune response in the lungs. Lymph node tissue from both the lung and the gut were collected from 84 deceased donors, spanning ages 11 to 93.

The first big observation was that lung lymph node tissue from humans became increasingly black as a person got older, but lymph node tissue taken from the gut did not show the same age-related changes. Zooming in on the lung lymph nodes Farber said it quickly became clear that pollutant particles were found inside crucial immune cells.

Donna Farber / Columbia University Irving Medical Center

“These immune cells are simply choked with particulates and could not perform essential functions that help defend us against pathogens,” Farber said.

Air pollution particles were particularly found in immune cells called macrophages. These immune cells are like front-line soldiers in the lungs, destroying bacteria and sweeping away dead cells. Macrophages also act as crucial immune signaling cells, secreting molecules to call in reinforcements from other immune cells.

These new findings indicate air pollution particles can accumulate in the lung nodes that produce macrophages, and this impairs their function. So over long periods of exposure to air pollution our lungs ultimately decline in their ability to battle pathogens, leaving us more susceptible to respiratory infections.

According to Farber, these findings are not intended to be a singular definitive explanation as to how age makes us more vulnerable to diseases like influenza. However, the study provides robust evidence decades of exposure to air pollution can weaken our immune defenses.

“We do not know yet the full impact pollution has on the immune system in the lung, but pollution undoubtedly plays a role in creating more dangerous respiratory infections in elderly individuals and is another reason to continue the work in improving air quality,” Farber stressed.

James Kiley, from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), said the findings are interesting and help us understand why the elderly are more susceptible to lung disease. Kiley, who didn’t work on the study himself, also added the study supports a greater push to address air pollution, something Farber and colleagues directly raise in the study.

“The specific effects of pollutants on lung inflammation and asthma in certain individuals or within certain geographic regions have been documented,” the researchers concluded in the study. “The effects of pollutants on neurodegenerative disease are also well documented and neuroinflammation is implicated in this process. We therefore propose that policies to limit carbon emissions will not only improve the global climate, but also preserve our immune systems and their ability to protect against current and emerging pathogens and to maintain tissue health and integrity.”

The new study was published in the journal Nature Medicine.

Source: Columbia University Irving Medical Center

Source of Article