Digital transformation could dramatically transform the traditional roles of crew members on ships as machines manage traditional navigational operations onboard.

Image: Wärtsilä Voyage

A number of companies are investing in autonomous and semi-autonomous craft to navigate roadways and traverse the airways of the future. At the same time, autonomous solutions are revolutionizing the maritime market, bringing machine learning and artificial intelligence seafarers into the fold as companies rethink shipping in the digital transformation age. As waterways become increasingly automated what will these changes mean for human seafarers?

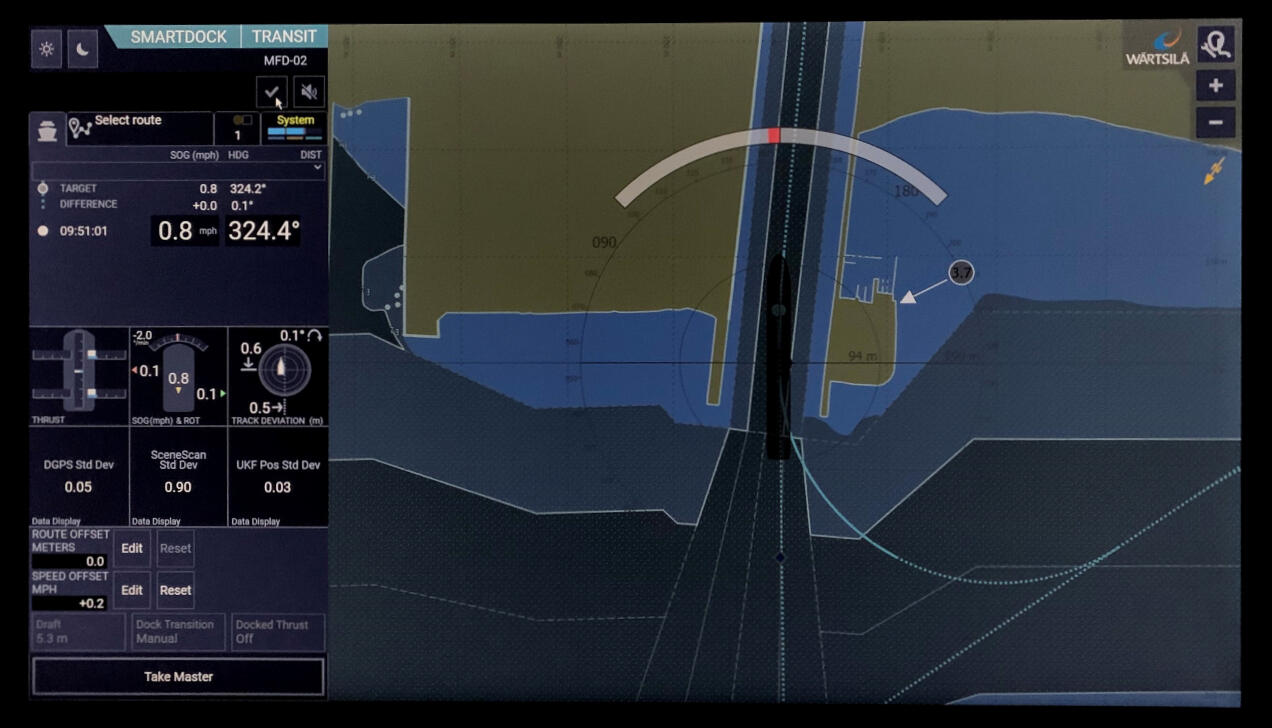

In a recent blog post, autonomous shipping solutions provider, Wärtsilä Voyage, described its retrofit of the American Courage, a 194-meter bulk freighter that operates along the Cuyahoga River. With these autonomous capabilities, the American Courage became the “largest ship ever to perform automatic dock-to-dock operation,” according to the company.

SEE: TechRepublic Premium editorial calendar: IT policies, checklists, toolkits, and research for download (TechRepublic Premium)

Navigating this narrow stretch of the Cuyahoga comes with no shortage of spatial or logistical challenges whether its a human at the helm or an autonomous ship. Unlike the open water, which offers plenty of room for error, the fault-tolerance on this riverway is “extremely low,” explained Hendrik Bußhoff, a product manager at Wärtsilä Voyage.

“[There’s] literally just two or three meters [from] being too far left and being too far right, [that’s] the difference between you crashing into a bridge or not,” Bußhoff said.

The American Courage navigating the Cuyahoga River.

Image: Wärtsilä Voyage

Beyond the slim peripheral margins, the Cuyahoga also bisects the city of Cleveland and hosts both commercial and recreational crafts of varying sizes.

“The river would be a lot more benign if you were alone on the river. But you aren’t. Again, you’re in the middle of a million [person] city,” Bußhoff said.

Aside from the “paddle boats, canoes, speed boats, rowing skiffs,” he said there have been incidents where ships along this waterway have crashed into the bars and restaurants situated along the river bank.

Regardless of these seafaring challenges, the highly repetitive nature of this ship’s route makes it ideal for automation, Bußhoff explained.

“This stretch on the river is the same. It’s repeatable. So you can say, “Okay, let’s start there. Let’s automate the repeatable part first and focus on that operation up and down the river, again and again, and again,” he said.

The American Courage navigating the Cuyahoga River.

Image: Wärtsilä Voyage

To automate these operations and sense its environment, the American Courage uses a ship-based positioning system rather than a shore-based system. While GPS may be sufficient for car navigation there are pitfalls to consider.

For starters, Bußhoff said that GPS systems are not highly accurate and can be readily jammed with “dirt cheap” off-the-shelf components. To shore up these risks, the American Courage touts a secondary positioning solution which Bußhoff likened to the LiDAR systems used in the autonomous driving industry, albeit more rugged and with extended range.

“Basically, what it does is, it scans the river banks, the scenery, creates a map of that and then it can navigate within that map and the beauty is, now you are reliant on nothing which is outside your control. You have a scanner on the ship which scans the environment as it is,” he said.

Interestingly, the American Courage system uses both GPS and its onboard sensing system to enable autonomous navigation, according to Bußhoff, with some “clever software in the background” constantly checking these two methods to determine which is more reliable.

SEE: Drone vaccine delivery? Agile aircraft reimagine cold-chain logistics in rural North Carolina (TechRepublic)

Image: Wärtsilä Voyage

There’s also regulatory red tape to bear in mind with autonomous navigation whether on land or sea. As it is with driverless vehicles, he said, fully autonomous shipping is not permitted at the moment and doesn’t anticipate this changing “tomorrow.” There are still humans in the loop aboard the American Courage to intervene in the event of an emergency, but the nature of the traditional oversight role has evolved markedly.

“It’s more shifted from a do everything yourself function to a monitor the task execution function. But the human at no point is leaving the operation completely alone,” Bußhoff said.

The ship also has a manual override, which he described as a “really big, fat mechanical switch,” and, in the event of an emergency, a human onboard can break physical copper wires, reconnect a physical copper wire to regain complete “manual control as it used to be in the old days.”

Onboard a vessel festooned with its own sensing environment and a vast suite of autonomous tech, this acts as a more analog “break glass in case of an emergency” option.

“No matter how many computers you have crashing there and freezing there, you don’t have to click through menus of a freezing touch screen,” Bußhoff said.

Although humans have not fully handed the keys to the ship over to the robo-seafarers, autonomous capabilities are transforming the traditional roles of crew members on ships.

Historically, the captain controls the operation and the helmsman executes the rudder commands, Bußhoff said, but the automated solutions have changed this dynamic.

“We now have an automation system, which is executing the rudder command and the helmsman is bored,” he added.

Bußhoff said that we are now at the stage where discussions can be had about reassigning the helmsman to “make better use of the person and do other things on the ship” rather than have them on the bridge looking out a window.

Bußhoff, a trained captain, said that in the world of dynamic positioning (DP), there’s a saying that “boring DP being good DP,” referring to the point when the automated dynamic positioning system “perfectly handles an operational situation,” meaning the desired state has been achieved. This is followed by complacency, he explained, and this is when the “human should step out of the operation and leave the dull stuff to the machine”

“Supervision should be replaced by a self-monitoring capability and a clever alarm handling to call in the human when the boredom stops,” he said.

When asked whether these new roles existed as a net benefit or a net negative for onboard employees, he referred back to his seafaring background and said he sees this transformation as “entirely positive” because it allows seafarers to be responsible for the navigation as well as the maintenance and upkeep onboard.

“I have been really annoyed by the time we sometimes had to spend on the bridge on the middle of the ocean, looking out of the window where exactly nothing happened and I would have indeed [been] grateful if I could have handed this task over to a machine,” Bußhoff said.

Once the machine is at the helm, he could then be free to manage technical breakdowns or other problems on the vessel, he added.

“You want to keep your ship ship-shape. Yet, regulations are forcing you to look out of the window. It’s annoying sometimes because it’s just an element of the job but others are calling for your attention as well,” Bußhoff said.

Generational shortage and shifting priorities

Whether these autonomous shipping solutions will impact employment quality or totals remains to be seen, however, there are industry supply and demand considerations at play.

“It is not easy to go up and down the river in a manual operation and, basically, there is the situation [where] you have a bunch of great captains who can do this, and they are growing older and they have learned their skill over 10 years, 20 years, 30 years,” Bußhoff said.

As one generation of captains retires a new generation of captains would need to replace them. However, fewer people have sought employment in the seafaring industries in recent years.

“There’s a generation of seafarers following, which is, first of all, not that big. You may run into a simple manpower shortage,” Bußhoff said.

Moreover, the current generation may not be a group that wants to invest “30 years in mastering a skill and then doing it for 10 years,” he said. Instead, “generation PlayStation,” as he dubbed it, is more adept with automation, touchscreens and other technologies.

With experienced human knowledge exiting the industry and dwindling employees entering, these autonomous solutions could address both sides of the equation.

“You have basically the combination of a need to take wisdom out of the brains of experienced operators and feed it into a machine and then you do this [as] an operation,” Bußhoff said.

Also see

Source of Article