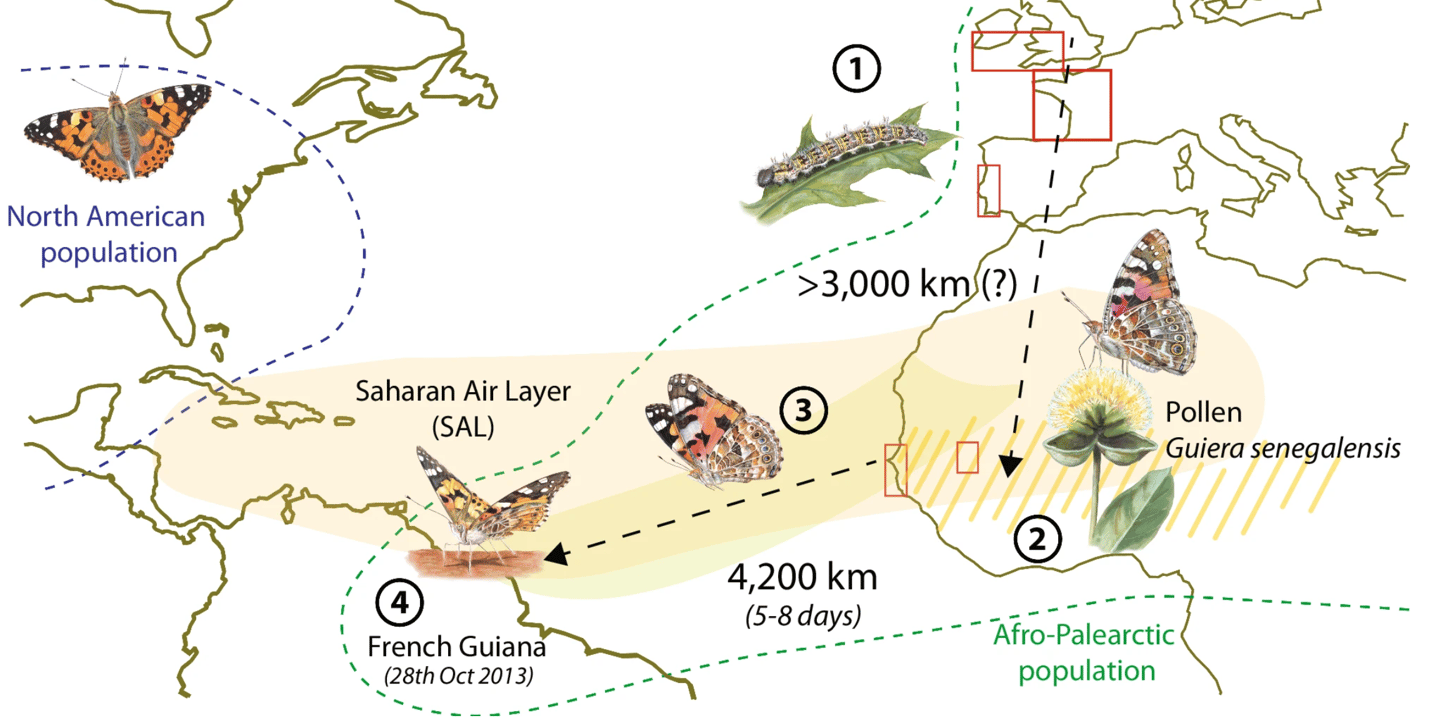

In a world first, scientists have discovered that painted lady butterflies (Vanessa cardui) have used favorable winds and a strategy of active flying and autopilot to fly across the world without stops, covering at least 4,200 km (2,600 miles). They believe the trip took five to eight days, potentially half the butterflies’ adult lifespan.

What’s more, these adventurous animals may actually be flying even longer distances – 7,000 km (4,350 miles) or more – from western Europe to Africa and on to South America. It upends what we know about butterfly migration and behavior.

“The butterflies could only have completed this flight using a strategy alternating between active flight, which is costly energetically, and gliding the wind,” said study co-author Eric Toro-Delgado, a scientist at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Barcelona. “We estimate that without wind, the butterflies could have flown a maximum of 780 km (485 miles) before consuming all their fat and, therefore, their energy.”

Researchers from the University of Ottowa and Spain’s Institute of Evolutionary Biology confirmed this stunning insight into the secret lives of butterflies using a suite of genetic detective work, after a flock of V. cardui were discovered on the Atlantic coast of South America, in French Guiana, far from the species’ known range.

While the species is widespread across the globe, a genomic analysis confirmed that the butterflies were closely related to those found in Africa and Europe, which meant they didn’t just migrate south over land from North America.

Then, an analysis of pollen grains that hitched along for the ride revealed that they originated from two plant species grown in tropical regions of Africa. From this, the scientists were able to track that the butterflies stocked up on nectar from these plants before jetting off on their ocean-crossing adventure.

Finally, the researchers used the butterflies’ wings to conduct a hydrogen and strontium isotope analysis – essentially providing a ‘fingerprint’ of where the animals originated. Pairing chemistry with ecology, they were able to match the results with suitable habitats and found that they most likely came from as far away as France, Ireland, the UK or Portugal.

“It is the first time that this combination of molecular techniques including isotope geolocation and pollen metabarcoding is tested on migratory insects,” said Clément Bataille, an associate professor at the University of Ottawa. “The results are very promising and transferable to many other migratory insect species. The technique should fundamentally transform our understanding of insect migration.”

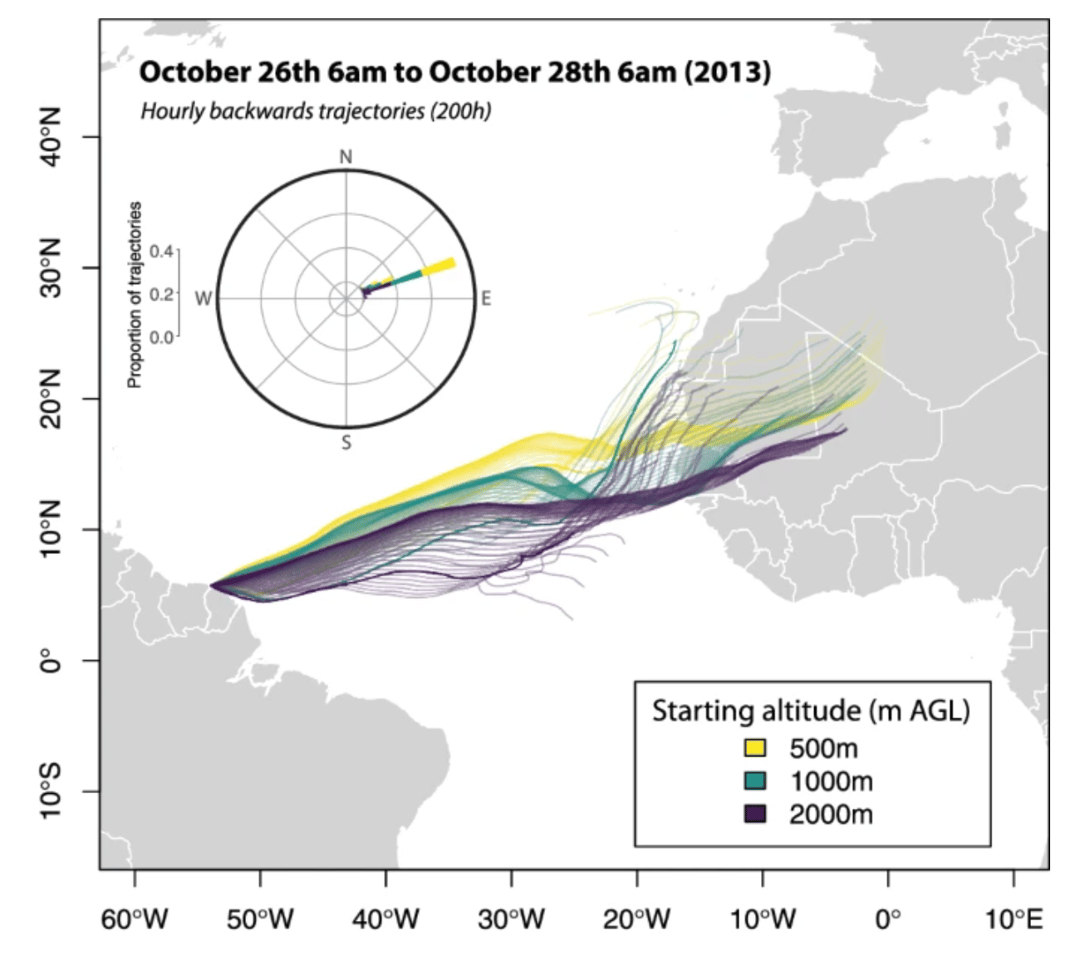

However, genetics and chemical analysis only formed part of the picture. The team then used historical records of wind trajectories leading up to the butterflies’ discovery in October 2013. They were then able to see that favorable trade winds made this epic transatlantic journey viable, which is an astounding new insight into the migratory behavior of insects.

“This study does a good job of demonstrating how much we tend to underestimate the dispersal abilities of insects,” said co-author Megan Reich, a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Ottawa. “Furthermore, it’s entirely possible that we are also underestimating the frequency of these types of dispersal events and their impact on ecosystems.”

And this transatlantic flight is no joyride for V. cardui – it’s more like the trip of a lifetime. The species has an adult lifespan of just two to four weeks, during which they invest all their energy in reproduction. As such, this journey appears to be an important strategy in species survival.

Their flight path made use of the Saharan air layer, a seasonal atmospheric event that sees dry, dust-laden air amass over the African desert in late spring, summer and early fall. It moves across the North Atlantic Ocean and every three to five days dumps particles over South America, fertilizing the Amazon in the process. Now scientists know that this dust cloud also aids the flying capabilities of organisms like these butterflies.

While not to take away from the impressive feat of these long-distance insect travelers, this study also sheds light on previously unknown aerial corridors used in migration, and how, due to climate change, these may increasingly be used as invisible ‘superhighways’ by many species seeking out optimal environments.

It also challenges beliefs that, due to their fragile wings, butterflies generally are not fans of windy conditions.

“It is essential to promote systematic monitoring routines for dispersing insects, which could help predict and mitigate potential risks to biodiversity resulting from global change,” said co-lead author Gerard Talavera, from the Institute of Evolutionary Biology.

Recently, butterflies were also found to be among the billions of insects that migrate south through a narrow mountain pass in Europe, seeking out warmer conditions in the region.

“We usually see butterflies as symbols of the fragility of beauty, but science shows us that they can perform incredible feats,” added study co-author Roger Vila, a researcher at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology. “There is still much to discover about their capabilities.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: University of Ottawa

Source of Article