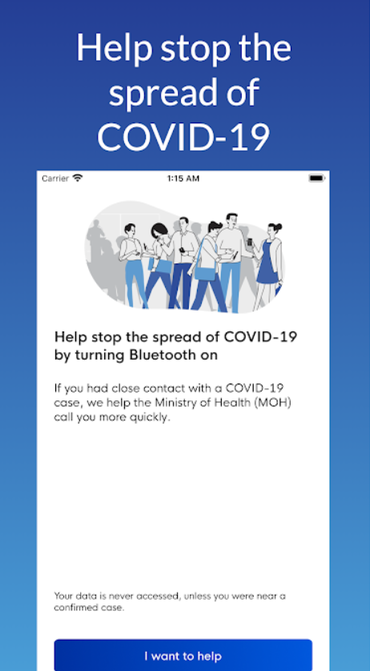

As more governments consider the use of contact tracing apps to prevent the spread of coronavirus, researchers say privacy will have to be at the forefront of efforts in order for civilians to use it.

Image: Ministry of Health Singapore

Governments around the world have begun exploring the use of contact tracing apps as a key means for tracking and reducing the spread of coronavirus. Contact tracing is a method for warning people when they have been exposed to someone who has contracted a serious illness like COVID-19. This method has previously been used to better understand and limit the spread of HIV, meningitis, and other diseases.

It also allows for governments or health authorities to identify individuals who may have been in close contact with an infected COVID-19 confirmed case.

SEE: Coronavirus: Critical IT policies and tools every business needs (TechRepublic Premium)

Traditionally, contact tracing required a very labour intensive process, Gnana Bharathy, a systems and modelling lecturer at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) told TechRepublic. But with technology such as smartphones, this has made contact tracing more efficient and easier to perform.

“Now, it is possible to do [contact tracing] through mobile phone data — that is assuming people seldom part with their phone. Therefore, you could take the signals and then see which signals are coming into contact with devices owned by people who have contracted COVID-19,” Bharathy explained.

“It’s essentially the identification of the signals that actually come into contact with any non-risk signal. This particular view is quite helpful from a health perspective because this is one of those illnesses that can even finish asymptomatically.”

SEE: Coronavirus having major effect on tech industry beyond supply chain delays (free PDF) (TechRepublic)

Rachael Falk, CEO of the Cyber Security Cooperative Research Centre (CSCRC), said with a serious public health crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, digital contact tracing is helpful as positive cases need to be identified quickly, and particularly if the patients involved are unable to communicate with those who they come into contact with.

” data-credit=”Image: Ministry of Health Singapore” rel=”noopener noreferrer nofollow”>

Singapore’s TraceTogether application

Image: Ministry of Health Singapore

“Having an asset record a timestamp and a period of time is going to be better than our memory … I think that’s a good thing and particularly for highly infectious public health issues,” Falk said.

In Singapore, the government has already released a contact tracing app, called TraceTogether, which traces the location and movements of individuals via mobile phones. Australia is currently working on a similar app that is based on the Singaporean app’s source code.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison said last week that using location information may be necessary to save lives and livelihoods.

“If that tool is going to help them do that, then this may be one of the sacrifices we have to make,” Morrison said last week.

On the industry side, Google and Apple have also been working on contact tracing — with their aim being to provide governments and researchers with as much information as possible to understand the spread patterns of coronavirus.

Apple and Google’s iteration of contact tracing entails creating application program interfaces (APIs) that would help public health authorities design apps with contact tracing capabilities. These apps would then be available in both Apple’s App Store and the Google Play store.

Belal Alsinglawi, an AI modeller for COVID-19 and data science lecturer at Western Sydney University, said Google and Apple’s contact tracing efforts would save time and resources in developing applications to track the virus’ spread, as well as give a bigger data picture regarding the pandemic’s impact.

SEE: COVID-19: How artificial intelligence can help companies plan for the future (TechRepublic)

He explained that algorithmic forecasts of the COVID-19 pandemic — especially AI-powered ones — could be much more accurate, but there has been a lack of data available. Due to this, most models used by governments for tracking and forecasting have not relied on AI.

“[AI predicative methods] involve finding trends in past data, and using these insights to forecast future events and there’s currently too few Australian cases to generate such a forecast for the country, with this being the same for many other countries too,” Alsinglawi said.

“Once we have enough data inputs about COVID-19, it will facilitate the mission for AI researchers to develop a predictive framework for the future epidemic events, and as a result, more lives being saved.”

The privacy conversation around contact tracing

The sensitive nature of medical information, collected from contact tracing, means that ensuring its privacy is particularly important. Due to this, plans to roll out contact tracing apps have not been without their fair share of critics, who have expressed concern that these apps do not have enough substance on the privacy and data protection fronts.

Addressing these concerns, Australia’s Minister for Government Services Stuart Robert said on Monday that so long as contact tracing apps do not have geolocation, it would not be known what is happening when a block of 15 minutes or more has been logged between two people.

“All we care about is who the person was next to … because there’s no geolocation, no one knows where the young person was or what they were doing, there’s no surveillance at all. It’s simply who they were near from a health point of view,” Stuart said.

A day later, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison said Australia’s upcoming contact tracing app would put data into an encrypted national store that is only accessible by the states and territories’ “health detectives”.

“The Commonwealth can’t access the data. No government agency at the Commonwealth level, not the tax office, not government services, not Centrelink, not Home Affairs, not Department of Education, not childcare — the Commonwealth will have no access to that data,” Morrison said.

SEE: COVID-19: How cell phones are helping to track future cases (TechRepublic)

Falk, who is currently reviewing Australia’s COVID-19 tracing app alongside the Digital Transformation Agency (DTA), backed the government’s comments that Australia’s iteration of contact tracing would be reasonably secure and private.

“The moment when you upload the app and you enter that data, that data is actually sitting in your handset, so nothing is going anywhere at that stage at all,” she said.

“That data is sitting on your hands, along with the data of other people you might come into contact with for the period of time to satisfy a digital note being named in that app without a contact. But at that stage, that data is not going anywhere,” she added.

When asked about the privacy concerns surrounding when data is temporarily stored inside the encrypted national store however, Falk declined to comment as testing around the app was still in progress.

Falk did acknowledge though, that any participation in using contact tracing apps should be voluntary, with Australians being allowed to take a conservative approach to protecting their online security and privacy if they wished to do so.

“From my perspective, I’ll be [using TraceTogether], but it’s opt-in and I recognise it is up to the individual’s approach. I think it’s right that Australians take a conservative approach to protecting their online security and privacy,” Falk said.

The Director of the University of Western Australia Centre for Software and Security Practice, David Glance, took a different perspective, telling TechRepublic that while it was reassuring to see the CSCRC and DTA perform security tests on Australia’s contact tracing app, there will always be privacy concerns due to the role health authorities have in collecting and using the information gathered.

“You’ve got to trust the implementation of infrastructure performed by the health authorities, which I don’t. They’re notoriously bad at running infrastructure, especially for something like this. And so, I think that’s the fundamental problem,” Glance said.

Previous data projects created by Australia’s health authorities, like My Health Record, have been lambasted for having a lack of security measures.

Glance added that Singapore’s version of TraceTogether, which Australia’s contact tracing will be based upon, uses keys that are generated by its health authority and “potentially gives access to the data on your phones”.

“They have the IDs of people who they are tracing so that’s great because that enables your authorities to quickly work out who’s been exposed and how to get in contact with the people who have been affected.

“But that means, essentially, you’re relying on the government producing a version of the application that doesn’t do other things … we have legislation in Australia that allows people to do that so what’s to say that the government doesn’t use this app, once it’s on your phone, to target you for keyboard login or to infiltrate your messaging or anything else?”

Is there a middle point?

With governments, such as Australia, already set on implementing contact tracing, Dr Mahmoud Elkhodr at Central Queensland University noted that while there will never be a “perfect solution” for privacy, there are various mechanisms that could be applied to improve the balance between privacy concerns and the public benefit.

“The right to be forgotten also known as the ‘right to erasure’ is an EU rule which gives EU citizens the right to request deletion of their personal data from Internet companies such as Google. In Australia, this law is non-existent. So perhaps the first measure the government should take to preserve the privacy of Australians when using the TraceTogether app is to draft legislations and implement features that allow them to simply delete their location information from the app,” Elkhodr said.

Elkhodr also proposed that governments should make their contact tracing applications open source if they are serious about addressing the privacy concerns.

“This enables transparency and provides the public with much needed assurances. The government should also ensure that the application will not be used outside its intended scope such as penalising non-essential travel,” he said.

SEE: COVID-19 demonstrates the need for disaster recovery and business continuity plans (TechRepublic Premium)

Currently, Singapore’s TraceTogether app is not open source software and is not subject to audit or oversight, however, the island nation committed to doing so last month.

Regardless of what security measures are put in place however, Elkhodr said the effectiveness of contact tracing apps would simply come down to whether people trust putting their data in the hands of government.

Glance, meanwhile, said that contact tracing is not a “silver bullet” even if it is successful.

“Testing is obviously the key to controlling disease and it has to be widespread testing.

“The fundamental issue is really, again, going back to what do you do next? Apps are not going to help us with that — they’re not going to help us if we decide to open the border. There is going to be a certain amount of infection. The key to that is testing,” he said.

At the time of writing, the World Health Organization reported that there have been over 2.4 million confirmed cases, with over 163,000 fatalities as a result of the virus.

More coronavirus: Tracking and predicting how it will spread

Verizon Media builds search engine to help researchers find COVID-19 documents

The search engine was developed using Verizon’s Vespa big data processing technology and comes in response to a nationwide open research data set challenge.

Robots assisting factory workers and retailers in fight against coronavirus

Robots are playing an integral role in efforts to keep essential workers safe and transform factories for the effort against coronavirus.

Mayo Clinic uses self-driving shuttles to transport coronavirus tests on Florida campus

Autonomous vehicles are delivering food to quarantined communities, and robots are disinfecting hospital rooms in China due to COVID-19.

New daily charts map out which states have flattened the COVID-19 death curve

None of the states with the highest COVID-related death rates such as Washington, New Jersey, New York, California, Michigan or Louisiana have flattened the curve. This data shows who has been successful.

Google Cloud launches new AI chatbot for COVID-19 information

The Rapid Response Virtual Agent program includes open source templates for companies to add coronavirus content to their own chatbots.

Coronavirus data story tracks hot spots around the world and in the US

Analyst used Microsoft’s Power BI and public data to visualize the rise and fall of the coronavirus country by country and state by state.

Source of Article