Researchers at MIT have observed “electron whirlpools” for the first time. The bizarre behavior arises when electricity flows as a fluid, which could make for more efficient electronics.

Like water, electricity is made up of discreet particles, so one might expect that they would both flow in similar ways. But while water molecules are big enough to jostle each other and flow together, electrons are much smaller, meaning they’re more influenced by their surroundings than each other.

However, it has been predicted that under ideal conditions – at temperatures close to absolute zero and in pure, defect-free materials – quantum effects should take over their movement and allow them to flow as an electron fluid with the viscosity of honey. If scientists could harness this, it could make for more efficient electronic devices where electricity flows with less resistance.

In the new study, the MIT team has observed a clear sign of an electron fluid – whirlpools. These are common structures in fluid flows but not something that electrons can usually produce, and as such they’ve never been observed before. The researchers spotted the electron whirlpools in crystals of tungsten ditelluride.

“Tungsten ditelluride is one of the new quantum materials where electrons are strongly interacting and behave as quantum waves rather than particles,” said Leonid Levitov, co-author of the study. “In addition, the material is very clean, which makes the fluid-like behavior directly accessible.”

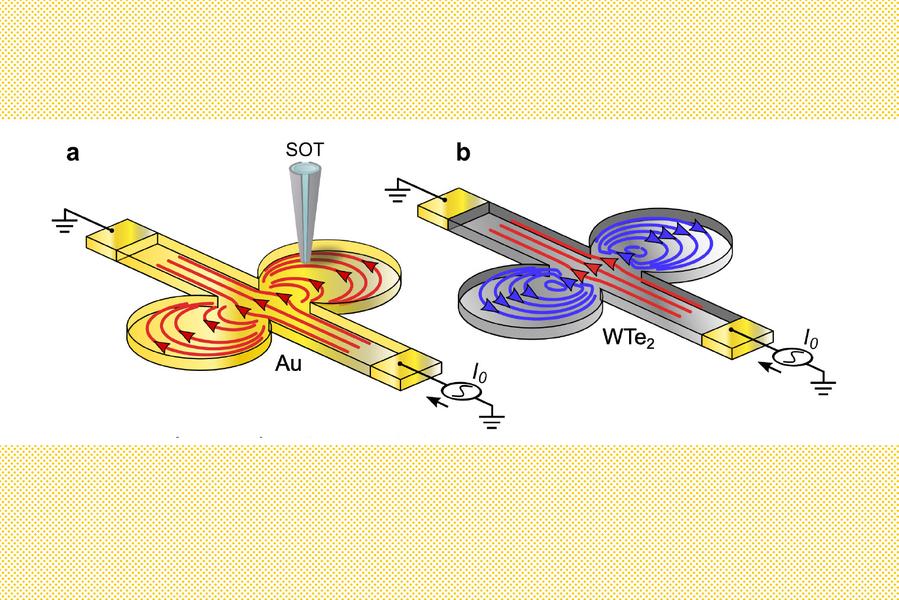

MIT

In this material, the team etched a narrow channel with a circular chamber on either side, then ran a current through it and measured electron flow. In standard materials like gold, the electrons would always flow in the same general direction, even as they spread out into the chambers and then came back into the central channel. But in the tungsten ditelluride, the electrons swirled through the circular chambers, reversing direction and creating whirlpools.

“Electron vortices are expected in theory, but there’s been no direct proof, and seeing is believing,” said Levitov. “Now we’ve seen it, and it’s a clear signature of being in this new regime, where electrons behave as a fluid, not as individual particles.”

The team says that this confirmation of a long-standing prediction could help scientists design more efficient electronics.

The research was published in the journal Nature.

Source: MIT

Source of Article