Research led by scientists associated with the American Museum of Natural History suggests that the giant reptiles of the age of the dinosaurs were descendants of a very tiny ancestor, shedding light on how the characteristics of dinosaurs and flying pterosaurs evolved.

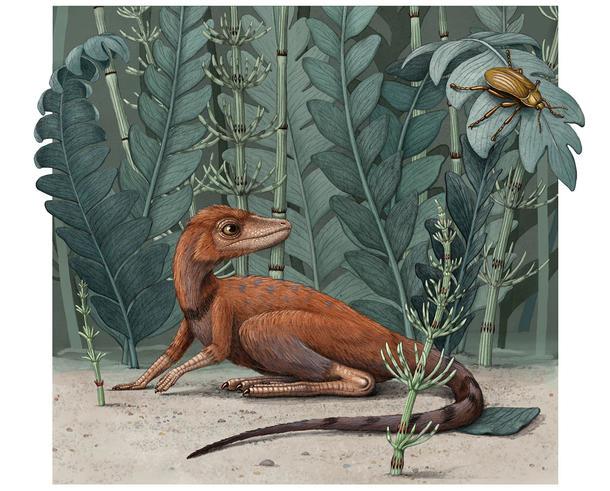

About 237 million years ago, during the Middle Triassic period, a 4-inch-tall (10-cm) insect-eating reptile lived in the primordial jungles of what is now Madagascar. Called Kongonaphon kely (tiny bug slayer), this animal sits near the root of Ornithodira, which is the part of the class Reptilia that includes the common ancestors of dinosaurs and pterosaurs.

The first Kongonaphon fossils were discovered in 1998 by a team of researchers led by the American Museum’s Frick Curator of Fossil Mammals, John Flynn. Until recently, such small reptiles were thought to be outliers, with the ancestors of dinosaurs being of a similar size to other archosaurs, the large reptile group that includes birds, crocodilians, non-avian dinosaurs, and pterosaurs, and that these later grew to gigantic proportions as the more familiar dinosaurs evolved. However, as more fossils were found and analyzed, Flynn says that another picture emerged.

“This fossil site in southwestern Madagascar from a poorly known time interval globally has produced some amazing fossils, and this tiny specimen was jumbled in among the hundreds we’ve collected from the site over the years,” says Flynn. “It took some time before we could focus on these bones, but once we did, it was clear we had something unique and worth a closer look. This is a great case for why field discoveries – combined with modern technology to analyze the fossils recovered – are still so important.”

Alex Boersma

Part of this analysis involved a study of tooth wear of Kongonaphon, which indicates that it ate insects. This shift in diet would cause its ancestors to miniaturize, but also increase its survival chances by filling an ecological niche not exploited by its carnivorous relatives. In addition, such small bodies would have a very large surface to volume ratio, meaning that they would get cold fast, Since the late Middle Triassic was a time of climate extremes, this suggests that they developed the fuzzy skin coverings found on many dinosaurs and pterosaurs, which later evolved into feathers.

“Discovery of this tiny relative of dinosaurs and pterosaurs emphasizes the importance of Madagascar’s fossil record for improving knowledge of vertebrate history during times that are poorly known in other places,” says project co-leader Lovasoa Ranivoharimanana of the University of Antananarivo in Madagascar. “Discoveries like this helps people in Madagascar and around the world better appreciate the exceptional record of ancient life preserved in the rocks of our country.”

The research was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Source: American Museum of Natural History

Source of Article