The vast, rocky Eastern Desert of Sudan, known to locals as the ‘Atbai,’ is a part of the Sahara Desert and home to nomadic groups. During 2018 and 2019, archeologists undertook fieldwork in the region as part of the Atbai Survey Project, aiming to investigate the relationship between indigenous nomads and ‘foreign’ Egyptian and Nubian cultures who ventured into this desert.

Cooper et al.

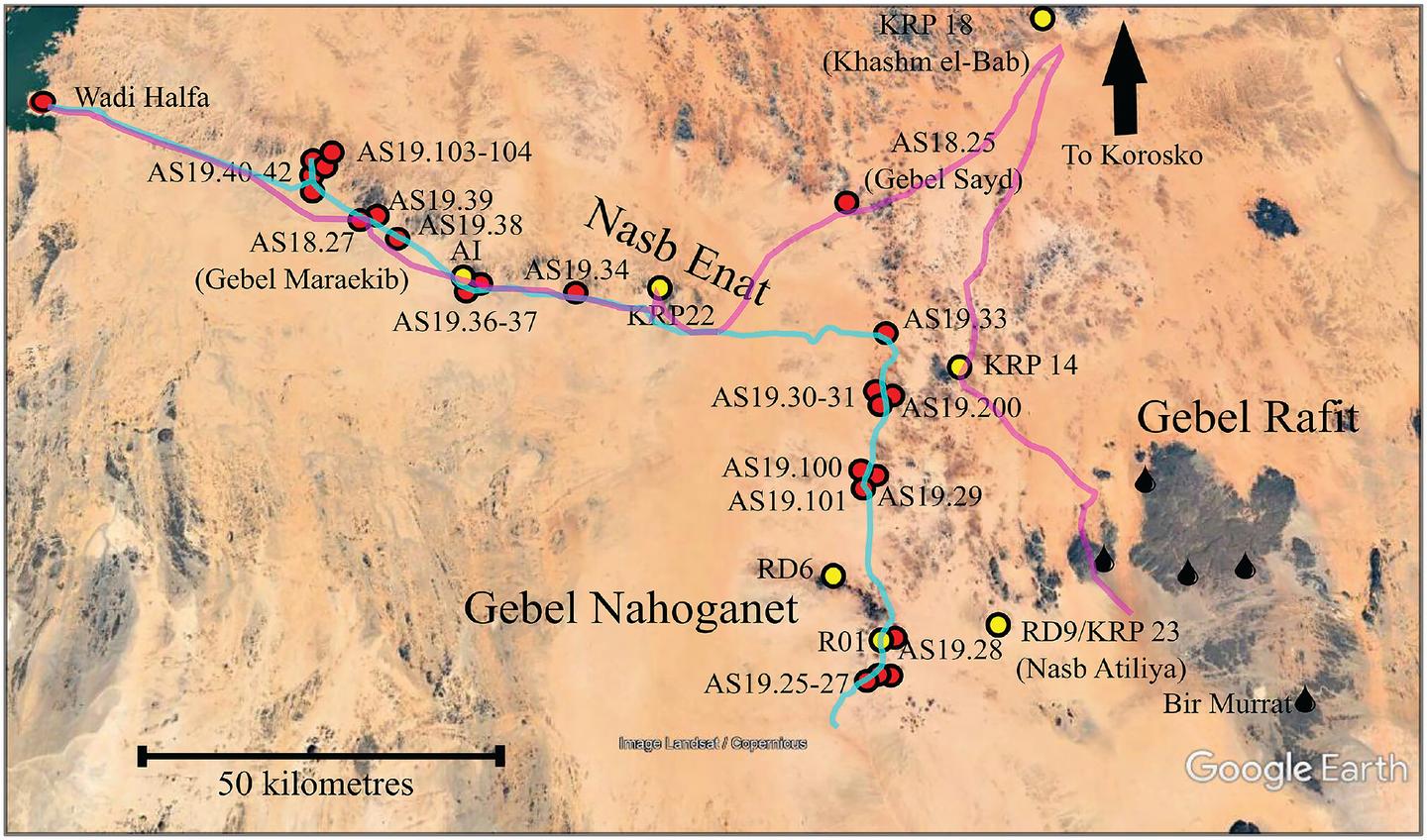

The archeologists examined rock art on hypothetical routes through the flat, hyper-arid deserts between Gebel Rafit, to the east, and Wadi Halfa, near Sudan’s border with Egypt. In Wadi Halfa, one of the driest and most desolate parts of the Sahara, the archeologists discovered 16 new rock art sites dating back 4,000 years. What surprised them most was that cattle featured in almost all of them.

“It was puzzling to find cattle carved on desert rock walls as they require plenty of water and acres of pasture and would not survive in the dry and arid environment of the Sahara today,” said Julien Cooper from the Department of History and Archeology at Macquarie University, New South Wales, and the study’s lead and corresponding author. “The presence of cattle in ancient rock art is one of the most important pieces of evidence establishing a once ‘green Sahara.’”

Cooper et al.

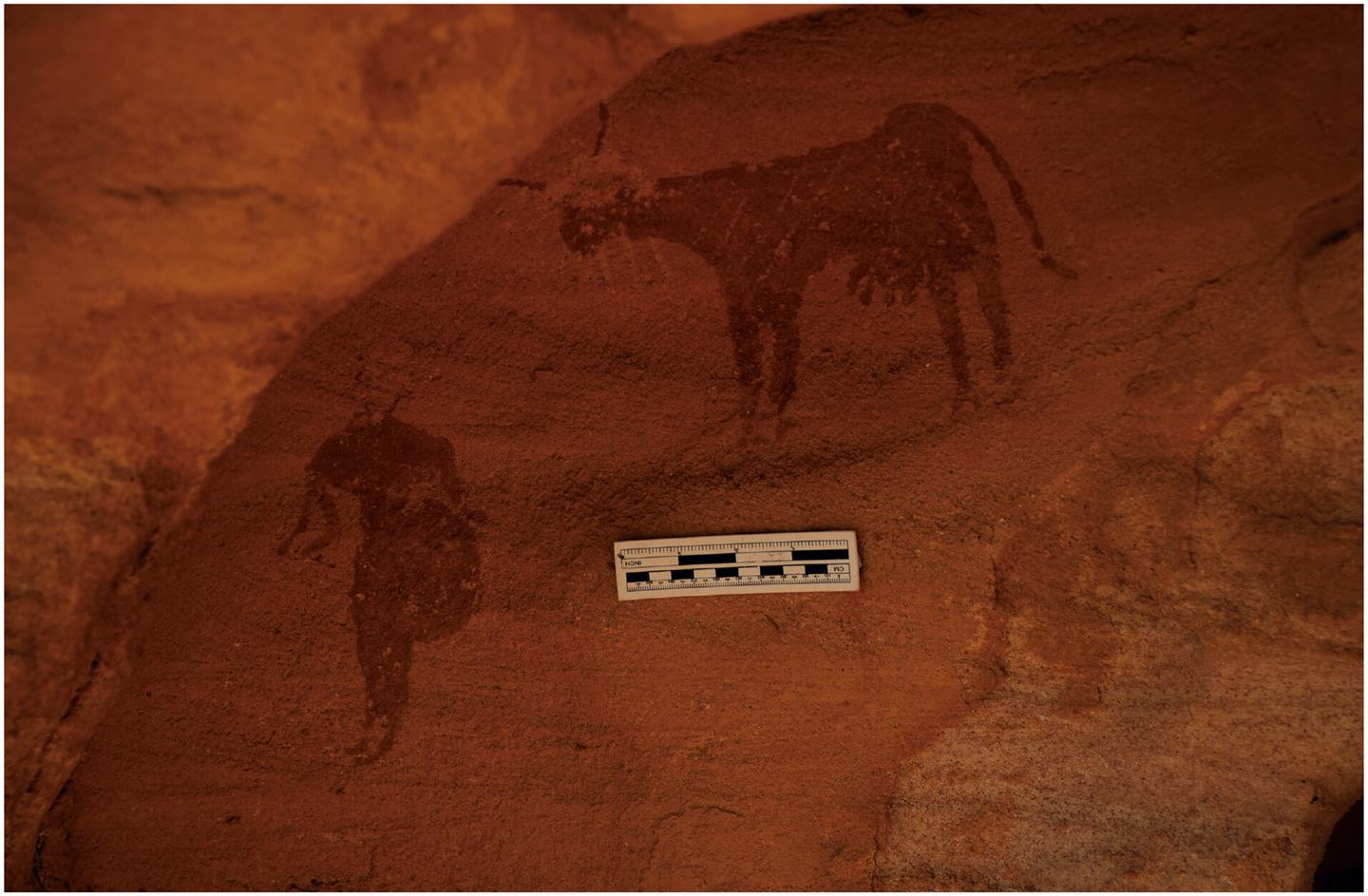

While painted rock art is a relative rarity in the Eastern Desert, the archeologists found at one of the sites a painted image of a cow with an enlarged udder beside a human who seems to be holding a vessel or other object. They say the scene depicted is likely representative of the act of milking, suggesting that cattle pastoralists – essentially, livestock farmers – lived in the region.

Painted cattle have also recently been discovered at Wadi Rasras, east of Aswan in Egypt. Those depictions include a cow with a swollen udder, raising the possibility that a pastoralist rock-art style existed across the entire Atbai. And the study’s authors had previously discovered a hunting scene and representations of cattle, antelopes, and giraffes at a site named ‘Gebel Sayd,’ noting a hunting scene and representations of cattle, antelopes, and giraffes.

The researchers say the newly discovered rock art paints a very different picture of the Sahara Desert, as a savanna complete with pools, rivers, swamps, and waterholes home to various fauna. Nowadays, the area receives almost no rainfall. Wadi Halfa, for example, receives a mean annual rainfall of 0.02 inches (0.5 millimeters), but rain often doesn’t fall on the ground for many years.

Bijanka Zubonja/Macquarie University

The so-called ‘African humid period,’ which saw an increase in summer monsoonal rainfall, is thought to have begun around 15,000 years ago. At the end of the period, around 3,000 BCE, the resulting lakes and rivers started drying up, the area was replaced by sand, and many human inhabitants headed closer to the Nile.

“The Atbai Desert around Wadi Halfa, where the new rock art was discovered, became almost completely depopulated,” said Cooper. “For those who remained, cattle were abandoned for sheep and goats. This would have had a major ramification on all aspects of human life – from diet and limited milk supplies, migratory patterns of herding families and the identity and livelihood of those who depended on their cattle.”

The study was published in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology.

Source: Macquarie University via Scimex

Source of Article