Regardless of what you may think of insects – if you even think about them at all – they make up around 90% of animal species on the planet and without them we’d see the collapse of ocean and land ecosystems that could ultimately lead to the end of all life on Earth. And most of the good work they do is essentially invisible to us.

It’s fair to say, entomologists and ecologists have done a terrible job with bug PR.

However, fascinating research out of the University of Exeter has discovered an epic migration superhighway used by millions of diverse insects every year in what is essentially a March of the Penguins for tiny flyers. It not only shows the incredible feat of these insects that fly some 1,000 miles annually from northern Europe to warmer climes in the south for winter each year, but that without such a migration route there could be disastrous consequences for life up the food chain.

Over four years in fall, researchers tracked the long migration of 17 million insects along this aerial highway – a gap between two high peaks, just 30 meters (98 ft) wide, in the Pyrenees mountains, between France and Spain. Estimating annual ‘bioflow,’ the scientists believe this mountain range would see at least 14.6 billion day-flying insects traveling the picturesque route every year.

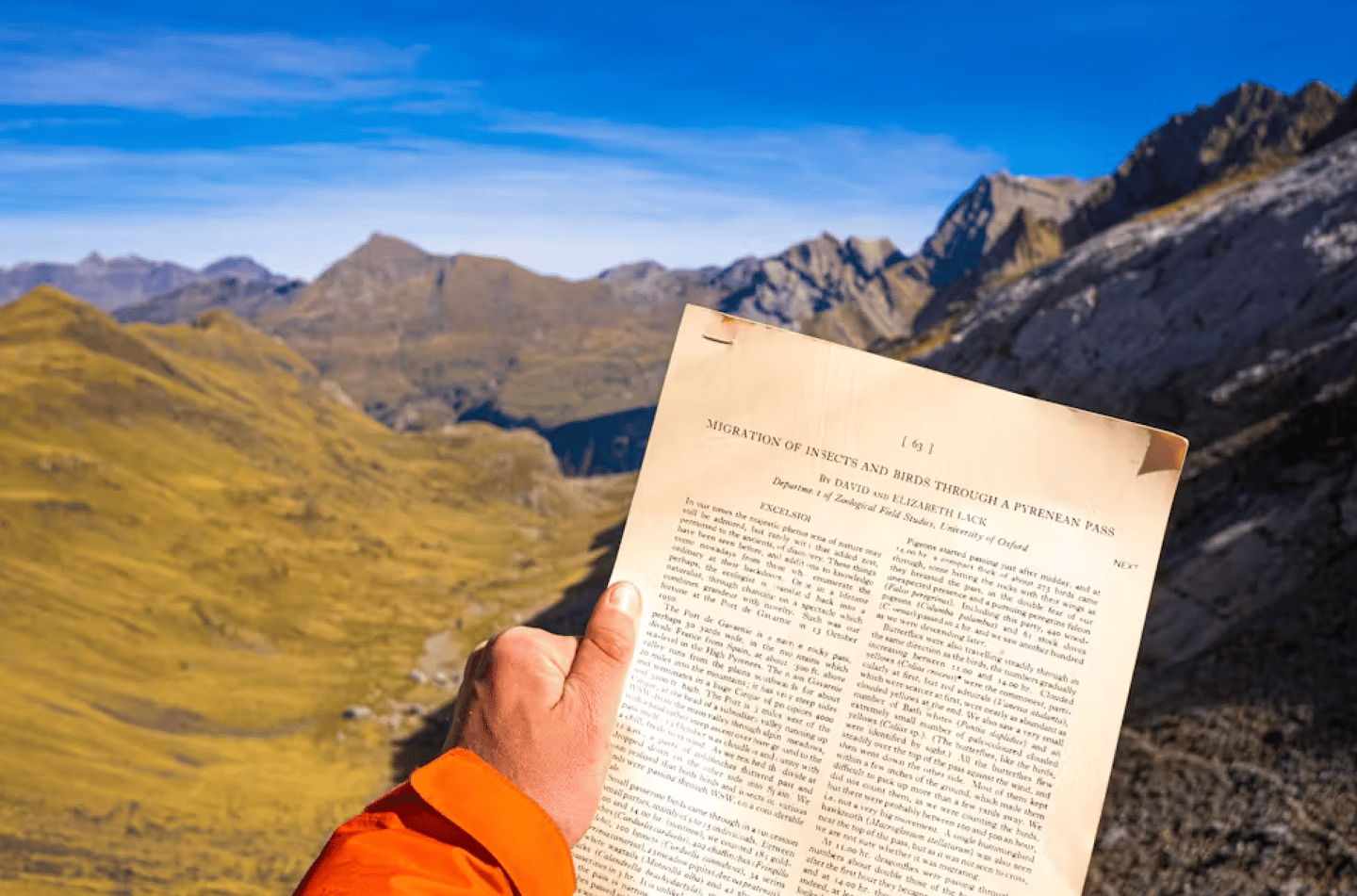

“More than 70 years ago, two ornithologists – Elizabeth and David Lack – chanced upon an incredible spectacle of insect migration at the Pass of Bujaruelo,” said Will Hawkes, from the Centre for Ecology and Conservation at the University of Exeter’s Penryn Campus in Cornwall. “They witnessed remarkable numbers of marmalade hoverflies migrating through the mountains, the first recorded instance of fly migration in Europe. In 2018, we went to the same pass to see if this migration still occurred, and to record the numbers, species, weather conditions and ecological roles and impacts of the migrants.”

Will Hawkes

Because of the difficulty in counting such small, fast-moving creatures, the researchers used video to count migrants, their own eyes to clock passing butterflies, and a flight-intercept trap to better identify species cruising through the Pass of Bujaruelo, some 2,273-m (7,457-ft) above sea level.

“What we found was truly remarkable,” Hawkes said. “Not only were vast numbers of marmalade hoverflies still migrating through the pass, but far more besides. These insects would have begun their journeys farther north in Europe and continued south into Spain and perhaps beyond for the winter. There were some days when the number of flies was well over 3,000 individuals per meter, per minute.”

And, yes, sometimes field research can involve standing between mountains, waving a bug net around, as this video below demonstrates.

“It was magical. I would sweep my net through seemingly empty air and it would be full of the tiniest of flies, all journeying on this unbelievably huge migration,” said Hawkes.

Catching migratory flies on a Pyrenean pass

This migratory feat is usually hidden from human sight, taking place at much higher altitudes. But the right conditions (warm, sunny and dry) with a low headwind pushes the insects lower through the pass.

“The combination of high-altitude mountains and wind patterns render what is normally an invisible high-altitude migration into this incredibly rare spectacle observable at ground level,” said research lead Karl Wotton. “To see so many insects all moving purposefully in the same direction at the same time is truly one of the great wonders of nature.”

Will Hawkes

A majority of the count featured various fly species, and while butterflies and dragonflies are known to migrate, they formed just 2% of the population of travelers. The researchers observed common garden insects too, like the cabbage white butterfly (Pieris rapae), house fly (Musca autumnalis), and grass flies (Chloropidae), that measure just 3-mm long.

Importantly, close to 90% of the migrating bugs were pollinators, so traveling such a distance is crucial for genetic diversity in often increasingly fragmented patches of vegetation. There were also insects that are essential pest controllers, like the aphid larvae-eating marmalade and pied hoverflies.

The migrants also provide an in-flight snack for birds such as chaffinches, goldfinches and swallows, which eat insects mid-air on their own-long distance trips.

“By spreading the knowledge of these remarkable migrants, we can spread interest and determination to protect their habitats,” said Hawkes.

The research was published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Source: University of Exeter

Source of Article