In 2023, Pew Research Center reported that 26% of Americans regularly got their news from YouTube. Because YouTube’s search results are affected by a user’s watch history, opening up the possibility of being presented with all sorts of content, users are likely to encounter misinformation, whether it’s unintentional or deliberate.

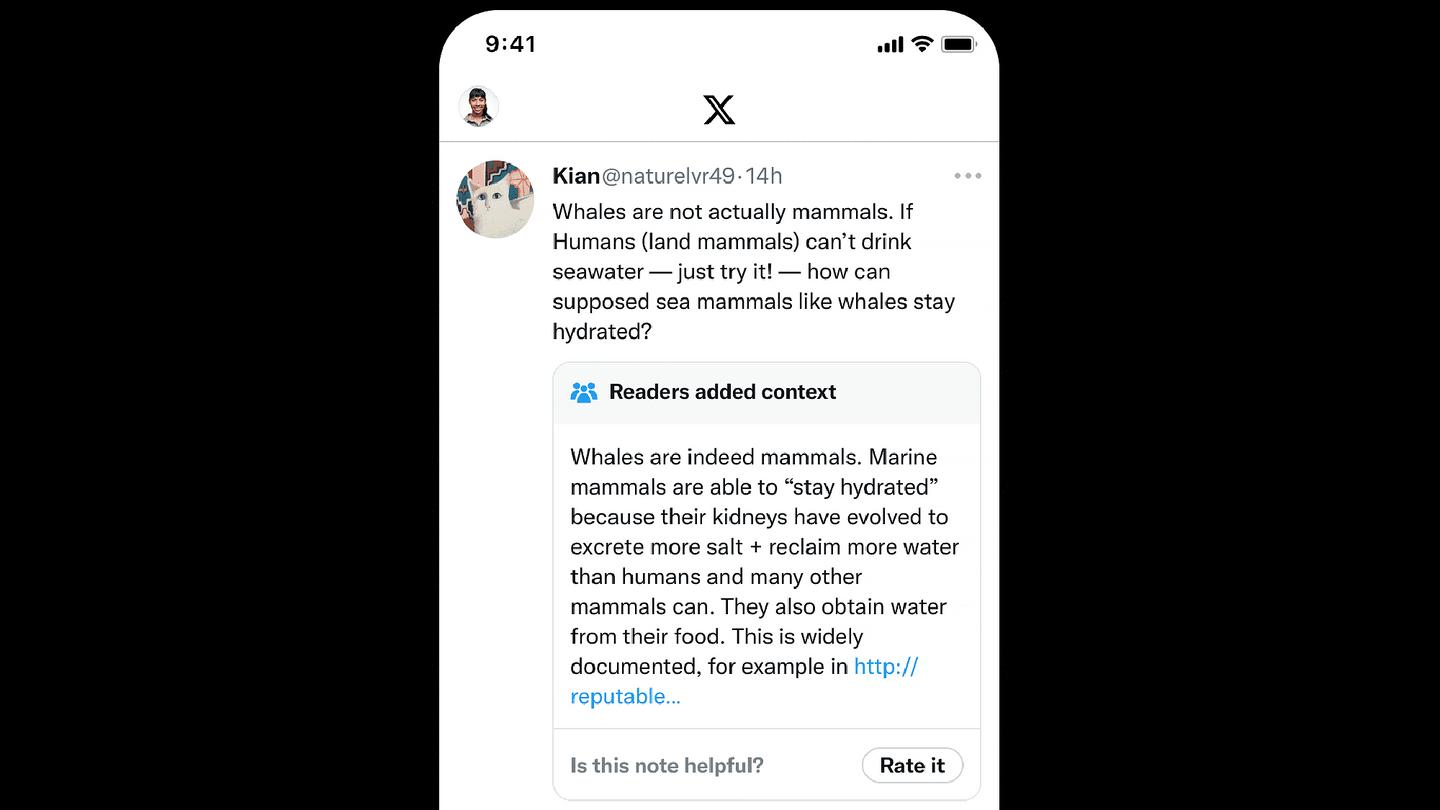

Compare YouTube to X, where there exists a feature called Community Notes. According to the X Help Center, the aim of Community Notes is “to create a better informed world by empowering people on X to collaboratively add context to potentially misleading posts.” It works like this: contributors leave a note on a post, and if enough contributors with other points of view rate that note as helpful, it’s shown publicly. (Community Notes contributors are X users who sign up to write and rate notes – the more there are, the more effective the program is.)

X

Seeing a gap that needed filling, researchers from the University of Washington (UW) developed Viblio. This browser extension enables YouTube users and content creators to assign credibility to a video via citations, much like those seen at the end of a Wikipedia post.

“The trouble is that a lot of YouTube videos, especially more educational ones, don’t offer a great way for people to prove they’re presenting good information,” said Emelia Hughes, the study’s lead author. “I’ve stumbled across a couple of YouTubers who were coming up with their own ways to cite sources within videos. There’s also not a great way to fight bad information. People can report a whole video, but that’s a pretty extreme measure when someone makes one or two mistakes.”

To inform Viblio’s design, the researchers studied how users interacted with existing ‘credibility signals’ on YouTube. By interviewing 12 YouTube users aged 18 to 60, they found out what factors helped them select and trust a video and what signals might confuse or be misleading. All participants relied on channel familiarity, channel name and production quality to assess a video’s trustworthiness.

Eight out of 12 (67%) relied on the video description, 58% went by how interesting the video looked, and 50% referred to the thumbnail. Interestingly, video quality, not really a mark of trustworthiness, was used as a proxy for it, even if the channel source was unfamiliar. The researchers noted that production quality compensated for a lack of other credibility signals.

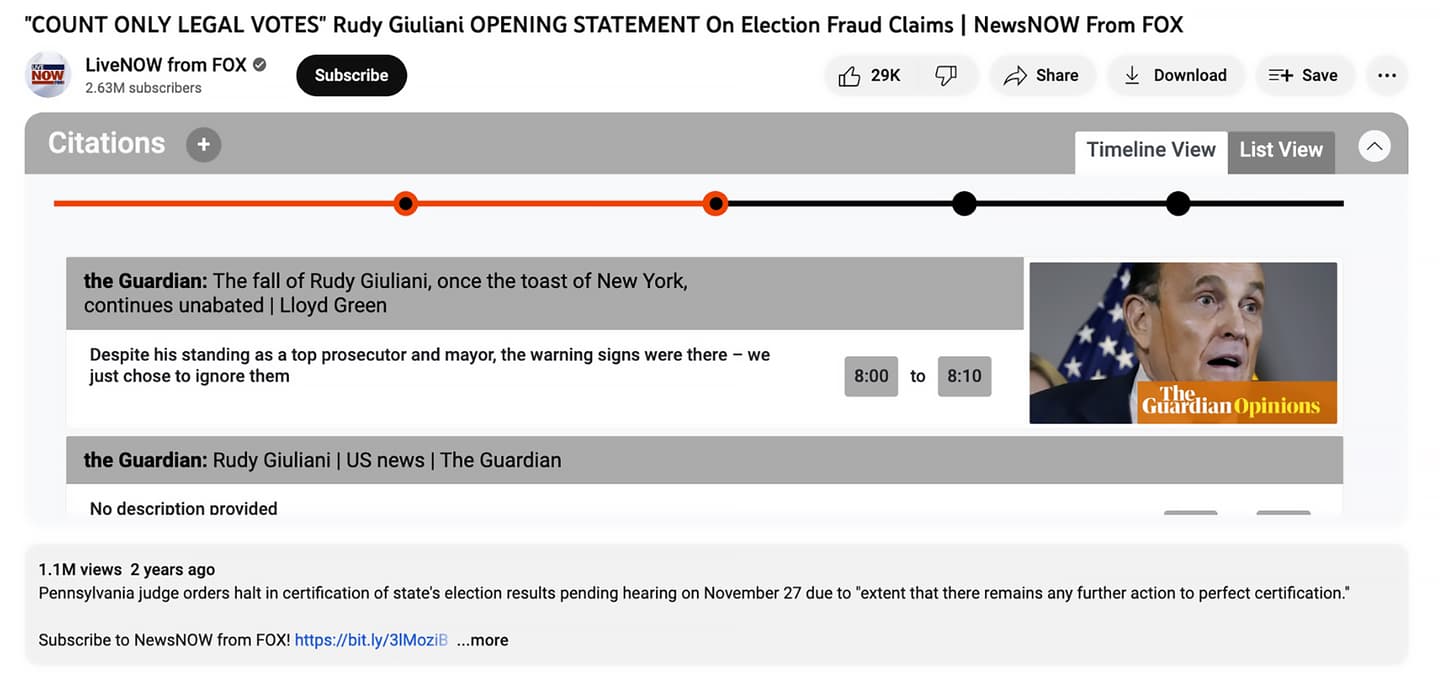

University of Washington

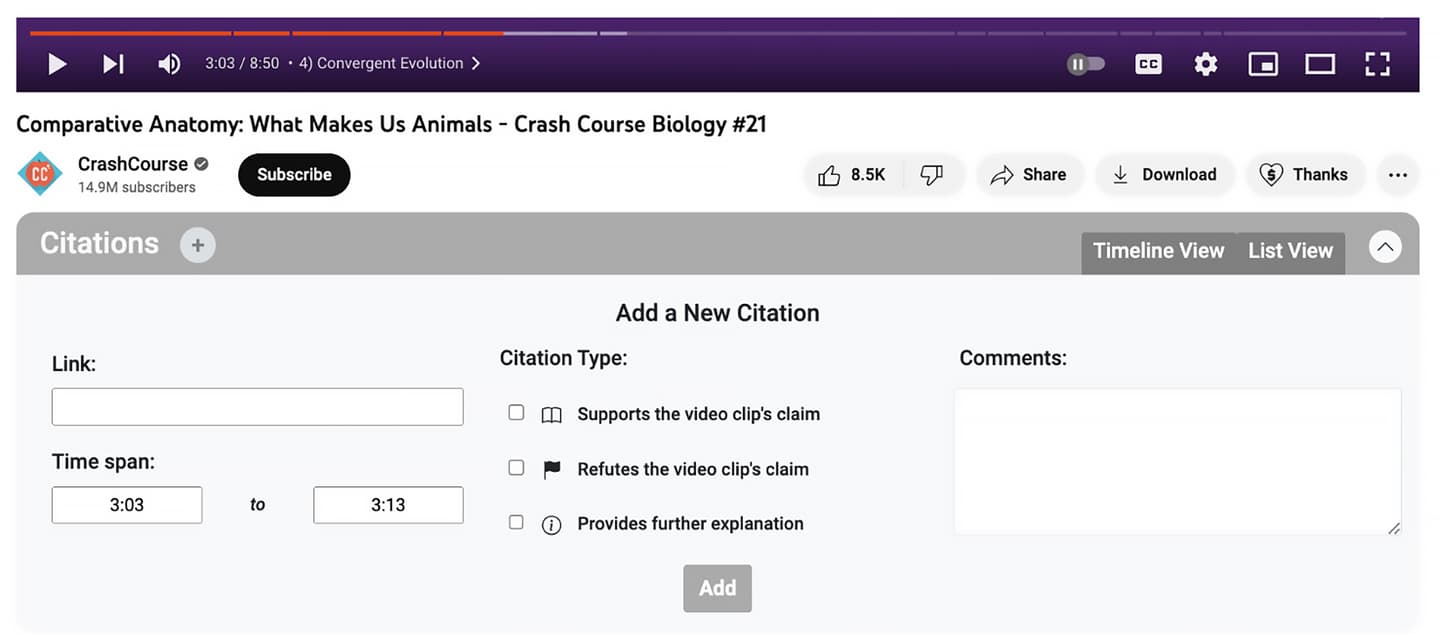

Viblio was built based on this information, allowing any user or content creator to insert a citation – or a number of citations – on a YouTube video’s timeline. The citations are displayed during video playback so that other viewers can access the information if they want to. The browser extension appears below the video and alongside the channel information, so it’s easily seen.

Users simply click a button to add a citation. They can then add a link and select the timespan their citation refers to. They have the option to add comments and can select the type of citation it is, which corresponds with a different colored dot in the video’s timeline: “refutes the video clip’s claim” (red dot), “supports the video clip’s claim” (green), or “provides further explanation” (blue).

University of Washington

The program was tested on 12 participants (different from the previous ones) aged from 18 to over 45. Over about two weeks, participants watched two to three videos a day totaling less than 30 minutes and rated the credibility of the video on a scale of one to five. Videos covered various topics, from informative (e.g. laser eye surgery, the history of cereal) to controversial (e.g. election fraud, COVID-19 vaccines, and abortion). The videos were from well-known sources, including Fox News and TED-Ed, as well as small local news stations and independent creators. Some of the videos had citations; some didn’t. Participants also had the ability to add their own citations.

The researchers received a wide range of feedback on Viblio’s usefulness in particular contexts. All participants agreed that Viblio would be useful for scientific or fact-based videos but not for entertainment-based videos. Some thought Viblio would be essential for controversial topics, while others were concerned about its misuse. Participants were unsure how they’d interpret citations on political videos and saw Viblio as a tool enabling balanced perspectives within news videos and facilitating neutral conversations. For many participants, the added citations changed their opinion of the credibility of certain videos.

The researchers are planning further study, extending Viblio to other video platforms such as TikTok or Instagram to see whether users are motivated enough to add citations. Then, they’ll look at whether a Community Notes-type approach could be incorporated into the program.

“Once we get past this initial question of how to add citations to videos, then the community vetting question remains very challenging,” said Amy Zhang, the study’s senior author. “It can work. At X, Community Notes is working on ways to prevent people from ‘gaming’ voting by looking at whether someone always takes the same political side. And Wikipedia has standards for what should be considered a good citation. So it’s possible. It just takes resources.”

Viblio sounds like an incredibly useful program. We hope that when it’s in its final form, Google thinks so, too, and adds it to YouTube. These kinds of initiatives can only work with a critical mass of users behind them, and the people that need this kind of fact checking the most are the ones least likely to install something like Viblio. This initiative can only help at scale if it becomes part of the global user experience. We can only hope!

The researchers will present their study findings at the Association of Computing Machinery (ACM) CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems in Honolulu, Hawai’i, on May 14. The study is available on the pre-print website arXiv.

Source: UW

Source of Article